Dockers refuse to load munitions for Anti-Soviet forces.

Reposted from London Radical History

When World War 1 came to an end, in November 1918, there were millions of men in uniform across Europe. After the initial nationalist fervour and pro-war enthusiasm that had seen mass enlistment in the first year or two, the war fever had largely abated. Mass slaughter, the stalemate of trench warfare, the horrors of soldiers’ experience – trauma, disease, cold, horrific wounds, as well as vicious military discipline, punishment of those who refused orders, were unable to fight any more… Many of those on the many fronts across the continent had been conscripted.

After over 17 million deaths and 20 million wounded, all most of those in the respective armies wanted to do was go home. Long years of fighting had largely engendered a widespread cynicism and disillusion – with the war aims, with the high command, with pro-war propaganda…

Out of this war-weariness, and inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917, (itself a product of army mutinies and revolts from a population enraged by the privation and poverty the war had aggravated), French and British army mutinies had erupted in 1917-18. Revolts, mutinies and uprisings among her allies left Germany mostly fighting alone by the beginning of November, and German mutinies had played a major part in Germany’s decision to open talks about ending the war with the allies…

But celebrations of peace were somewhat premature. And the British government, for one, was determined not to end the fighting, but to carry on the war – but against former ally, Russia.

After the October Revolution had overthrown the liberal government there, the new Bolshevik government had fulfilled one of the main aims of the revolution – to pull Russia out of the war.

This in itself enraged France and Britain, as it left Germany free to move large forces to the western front. But the overthrow of tsarism and then the bourgeois Kerensky government, and the beginnings of social revolution across Russia, also scared the pants off governments worldwide. And the leading allied nations were among the most worried. What if workers across Britain took Russia as an example? There had already been a huge upsurge in workplace organising, strikes, and social struggles as the war progressed… The British and French establishments were determined not only that radicals inspired by the Soviet upsurge be repressed, but to organise military intervention in Russia, to support the anti-revolutionary forces already fighting a civil war there, and if possible help them restore a more acceptable regime and crush working class power.

By this time of course, in Russia itself, the processes were already at work that would hamstring working class control and produce a Bolshevik dictatorship which would largely destroy any real communist potential within 3 years… However, it was all one to the western powers.

Plans to mobilise some of the millions conveniently still under orders and turn them against Russia were already underway long before the Armistice between Germany and the Allied powers was signed on 11 November.

An agreement had been drawn up in December 1917 between France, Italy and Britain to act against the Bolshevik regime, subsidise its opponents, and prepare ‘as quietly as possible’ for war on them.

Between February and November, British troops had already been sent to invade parts of Russia. Clauses within the peace agreement itself make it clear that troops were to be moved across Europe to the east, and ensured that free access to the Baltic and Black Sea for French and British navies would ease plans to invade Russian territory.

And immediately after the ‘peace’, plans were stepped up, along with a concerted propaganda campaign against ‘bolshevism’ in the press, designed to whip up support for military intervention.

But the plans involved reckoning on thousands of soldiers as pawns, and that British workers would have no view or no say in the matter. This was to be a serious miscalculation.

In the early months of 1919, there were still over a million British soldiers still in uniform, some in France but many more in army camps in this country. Many were expecting immediate demobilisation now the war was over; this expectation turned to frustration and then to eruptions of protest. Attempts to delay demobilization in order to facilitate intervention in Russia were certainly going on, but bureaucratic delays and simple problems of scale were also for sure causing backlogs and a slow process of sending soldier home. But in January 1919, a number of mutinies, protests and demonstrations in army camps in southern England and around London, demanding immediate demobilisation, broke out, causing serious alarm in government circles; especially as industrial unrest was increasing. Mutinies, links between discontent in the armed forces and on the home front had led to the Russian Revolution and to revolutionary uprisings still then raging in Germany, Hungary and elsewhere… The soldiers’ protests led to a swift acceleration of demobilisation, in order to scotch further rebellion in the ranks.

It also did make the government think more carefully about conscripting soldiers into an intervention force for sending to Russia. Clearly squaddies were not necessarily going to be happy to be pawns this time. Public opinion in Britain was also heavily against intervention in Russia…

The soldiers strikes of January certainly scotched the idea that a mass military force could be sent to help smash the Russian Revolution. But it wasn’t the end of the British government’s plans to support the ‘white’ armies fighting against the Bolsheviks.

And just as soldiers put their twopennorth in, organised workers would also have something to say on the matter.

From the early days following the Russian Revolution, British socialists of various stripe were enthused by the idea that workers were taking control of a major world power, and inspired by the thought of this spreading worldwide. The clear attempt by the British authorities to aid in smashing the revolution (while at the same time coming down hard against strikes and socialist movements here) drew fierce opposition from the British left.

In early 1919 the Hands Off Russia movement was born, an umbrella group uniting almost all sections of a (usually fairly fractious) left, to build resistance from within to any military campaign against Russia.

In fact, it united the British Socialist Party, the Socialist Labour Party, the Industrial Workers of the World (the British version of the famous ‘Wobblies’), the London Workers’ Committee (the capital’s equivalent of the Clyde Workers’ Committee – the shop steward-based organisers of the Red Clydeside era) and Sylvia Pankhurst’s (anti-parliamentary communist) Workers’ Socialist Federation A great deal of support was also given by George Lansbury’s Daily Herald (left labour) and its associated Herald Leagues, also then at their height.

As well as vigorous campaigning, some in the movement recognised that large amounts of munitions and other materials were likely to be needed for any Russian war. Even after the authorities reluctantly drew back from sending large forces of men to fight, they promised arms and other military supplies to the white Russian armies. This would have to be transported through the docks.

The Hands Off Russia movement involved lots of trade unionists and socialist activists: and especially in London, they had strong links with dockworkers in the East End; socialism and unionism was strong in the docks, and dockers were particularly militant around this time. The Hands Off Russia Campaign made a point of holding meetings around the docks, not just because there was a good receptive audience, but because these were workers who might be able to actually hold up the supply of munitions to the Russian reactionaries:

“Many of the comrades could be seen outside the London docks and shipyards selling ‘Hands Off Russia’ literature and our members were also selling inside. Day after day we posted up placards, stick backs and posters on the dockside, in ships and lavatories.” (Harry Pollitt)

Harry Pollitt, later Communist Party supremo, then a member of the Workers Socialist Federation, was an East End socialist activist, involved in this campaign. According to Pollitt after Lenin’s ‘Appeal to the Toiling Masses’, a call for international solidarity with the Soviet state – reprinted in Sylvia Pankhurst’s paper, the Workers Dreadnought, but banned by the Home Office – he kept hundreds of copies inside his mattress to avoid seizure if he was raided. Pankhurst handed out 1000s of copies around the docks and the East End. Pollitt credits Melvina Walker, a leading WSF member, as an important and tireless propagandist in the agitation against intervention: “She toiled like a Trojan. If on a shopping morning you went down Chrisp Street, Poplar, you could rely upon seeing Mrs. Walker talking to groups of women, telling them about Russia, how we must help them, and asking them to tell their husbands to keep their eyes skinned to see that no munitions went to help those who were trying to crush the Russian Revolution.”

The campaign slowly built up, including a one-day strike against intervention in summer 1919, co-ordinated with workers in other western countries, though only patchily supported. British aid to the reactionary forces continued. But subversive efforts to sabotage this process were at work…

In February 1920, Hands Off Russia meetings were widely reporting rumours recently printed in the Workers Dreadnought (though originally hailing from the German communist paper Rote Fahne) that the recent defeat of the white Russian reactionary general Yudenich had partly been due to the fact that British guns supplied to his forces had had parts removed – by workers in British armaments factories.

In March and April, learning that barges in the London docks were being loaded with munitions destined for ships bound to supply anti-Soviet forces, Hands Off Russia activists approached dockers to ask them not to load them. According to Pollitt, they seemed to ignore his pleas.. but an old docker approached him and told him not to worry. As the barges reached the ships in the North Sea, several cable ‘mysteriously snapped’, and much of the cargo was lost in the sea!

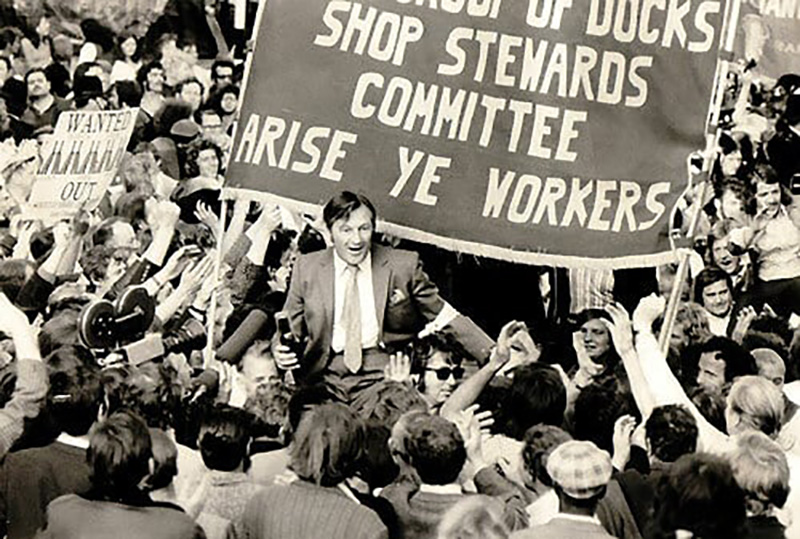

This was the immediate prelude to the best known action around this issue – the dockers refusal to load munitions on the Jolly George, in May 1920.

On 10 May, as the ship Jolly George was being loaded with a cargo labeled ‘OHMS Munitions for Poland’ in the East India Dock. Poland was at war with the Soviets and Polish armies had advanced deep into the Ukraine. The dockers at work there realised it was destined for the white Russian Armies. By this time, much of the guns had gone on board; but the coalheavers refused to stock the ship up with coal, unless the munitions were removed. While this situation led to a stand-off on the dockside, a deputation of dockers went to visit the Dockers’ Union general Secretaries, Ernest Bevin and Fred Thompson, and received assurances that the union would back a strike if the cargo remained on board.

The following day, the export branch of the Dock, Wharf and Riverside General Workers Union passed a resolution calling on the Transport Workers Federation and the Labour Party to support them in preventing the Jolly George from sailing… The Jolly George could not sail. Four days later the munitions were unloaded back onto the docks.

The dockers were not necessarily all in sympathy with communism, though many were inclined to some form of socialism. The Hands Off Russia had, however, tapped into a general feeling of revulsion at the idea of further warfare, and a sense that any cause the government was supporting was worth opposing… Without a doubt, the January 1919 mutinies and the campaign against the shipping of munitions helped to prevent the smashing of the Soviet Union.

For the moment, though, the actions of the dockers in May 1920 struck a blow that had huge significance.

According to Harry Pollitt, as the unloaded cases of munitions sat on the dock, on May 15th, “on the side of one case is a very familiar sticky-back, ‘Hands Off Russia!’ It is very small, but that day it was big enough to be read all over the world.”

Leave a comment