For almost thirty years, passengers have suffered delays, cancellations and skyrocketing fares. But could British Rail make a comeback?

The news that transport conglomerate FirstGroup would not be offered the opportunity to renew their franchise with the Department of Transport to operate the now infamous TransPennine Express rail service will come as little comfort, at least in the short term, to the thousands of passengers who have been suffering for years with overcrowding, cancellations, delays and eye-watering ticket prices on the franchise, which links Manchester and Liverpool with Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds, Sheffield and York.

It now means that approximately one in every four passenger rail journeys in this country is now provided by the ‘Operator of last resort’ – the Government. It joins other franchises, including Northern and the East Coast Main Line, in being operated by the State because the privateers charged with running them either handed the keys back and walked away or were unceremoniously relieved of their duties, asked to hand back the keys, collect their belongings and leave.

The rail network in this country has been the butt of jokes almost for as long as it has existed. The tales of British Rail’s late trains (“Eleven minutes late, signal failure at Vauxhall” as Leonard Rossiter declared when playing Reginald Perrin in the eponymously-titled 1970s comedy series) and curly sandwiches became part of the nation’s folklore. But British Rail is now a much yearned for publicly-owned utility which the majority of voters in this country would like to see make a comeback: The latest YouGov poll, taken on May 1st this year, shows that 66% of those polled either support or strongly support the public ownership of the train operating companies, with a measly 10% opposing to any degree the return of railways to public ownership.

British Rail’s history could be neatly carved into three distinct periods: From its inception in 1948 to around 1965, then from 1965 until around 1985, then from 1985 until its privatisation by the Major Government in the period from 1994 to 1997. When British Rail was formed under the Government of Clement Atlee, the infrastructure was in an incredibly shabby state and steam was still the dominant form of traction on Britain’s railways: BR inherited 20,000 steam locomotives at the time of nationalisation, was continuing to build them and would do for the next twelve years. This is in contrast to countries like Switzerland, whose railways were nationalised in 1900 and were building fully electrified railways from scratch as far back as the 1920s and were electrifying existing railways a decade before this.

What Britain’s railways needed more than anything was modernisation. However, the former pre-nationalisation ‘Big Four’ companies barely turned a profit from running railways and so were hesitant to invest in the upgrade of their networks and rolling stock. This fell at the feet of the State, who commenced to introduce huge changes to Britain’s railways, including electrification of large areas of the system and the ‘dieselisation’ of other sections – in essence a stop-gap to allow the replacement of steam engines with diesel trains, with those diesel trains eventually being replaced when the lines that they worked on were electrified (of course, not all of these plans came to fruition and diesel is still the primary means of traction on many routes in this country).

Huge areas of the rail network also saw similar upgrades to their signalling systems, with old mechanical signal boxes and their antiquated systems of operation replaced with colour-light signalling operated from ‘power boxes’ and electrical signal boxes covering far bigger areas of control then their mechanical predecessors.

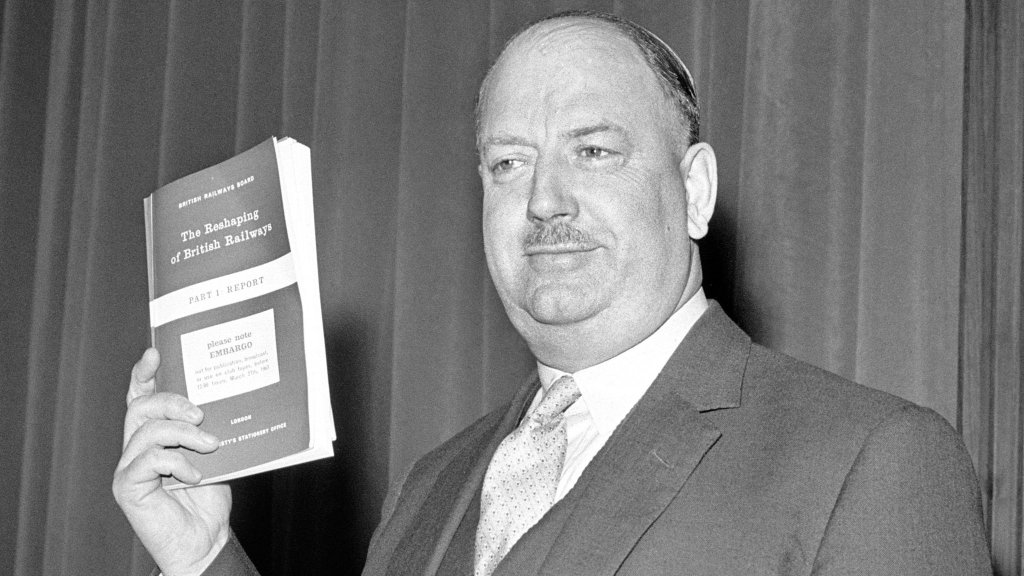

One extremely controversial step in the modernisation of the railways in this country was the Beeching Report, or to give it its correct name ‘The Reshaping of British Railways (Parts 1 and 2)’, which called for the closure of about a third of the entire passenger rail network on the premise that replacing these railway lines with bus routes would save an enormous amount of money and still provide people living on the branch lines that Dr Beeching proposed for closure a service, at least of sorts.

Coupled to this plan was the closure and conversion of hundreds of small goods and coal yards adjacent to stations into car parks, allowing people who had lost their railway lines to drive to the nearest station and take their train from there. However, what Beeching did not foresee was that people who lost their train services got into their cars, but rather than drive to the nearest railway station, they would simply drive all the way to their destination.

To compound this decision, British Rail ripped up hundreds of miles of track following the closure of the lines singled out in the Beeching Report, rather than mothballing them and the station buildings so that they could be re-opened in the future as and when required. The land that these lines occupied were often re-appropriated for house building, had roads built through them or were even converted into footpaths, meaning that towns which have seen subsequent expansion and population growth in the decades that followed could not see the restoration of their railway lines because of the cost and planning implications.

However, one step proposed within the Beeching Report which was extremely difficult to make a case against was his proposal to transform the transport of freight on Britain’s Railways. Beeching showed that half of the freight stations on the network could be closed and yet only 3% of gross receipts for freight would be lost: As far as Beeching was concerned, this proved that the cost of running these stations could never be recouped in income. He proposed to introduce huge freight terminals, which allowed the transport of containers of goods from docks and the like to a strategic location, where each container could be loaded onto a separate lorry and taken to their final destination. It is a model of freight logistics which remains in place to this day.

The fall in the rate of profit and the end of the post-war boom in around 1965 coincided with a decline in the passenger numbers on Britain’s railways through the 1960s, 1970s and into the early 1980s and the continued closure of lines. Lines which had initially avoided the Beeching axe eventually succumbed to closure, possibly most notably the line from Manchester to Sheffield (also known as the Woodhead line), a fully electrified railway which closed to passengers in 1970 and freight in 1981, while other lines remained open but were reduced from two tracks to one to save on maintenance costs. As the 1980s rolled on, stations like Broad Street in London were closed and demolished while other lines saw services cut and stations falling into severe states of disrepair as British Rail wrestled with repeated cuts in Government funding.

With British Rail managing to turn an actual profit in the years leading up to its privatisation, mainly through initiatives like the introduction of sectors like Network SouthEast and the sale of land, the Conservative Government of John Major, in the face of somewhat piecemeal opposition from the Labour Party, began what became a three year process of breaking up and privatising British Rail. Having sold off the nation’s water supply, gas and electricity boards, British Airways and our telephone system, it seemed fitting that our railways should also be in the Government’s cross-hairs. The model for British Rail’s privatisation was to separate the infrastructure (essentially the track and the signals) from the services (the passenger service providers and freight firms) and sell off the infrastructure firm as one entity (which became Railtrack), while the service provision would be awarded through a franchise bidding system.

The government believed that privatisation would bring the wonders of the free market to the decrepit and sclerotic entity that was British Rail. A privatised railway could invest in new trains and new technology, allow rail operators to compete, which would drive down fares, and open up new train services, connecting cities and towns previously unconnected. All in all, there was no way that the travelling public could lose.

What resulted in reality was a fragmented, bureaucratic and hellishly expensive system of operation, which spawned duplicate management structures for each individual company, destroyed national pay agreements and replaced them with local ones negotiated between the trade unions and each individual employer separately and created a labyrinthine system of delay attribution, where Railtrack and each train operating company would pit battle to deflect responsibility for delays, as delay attribution would result in fines paid from one to the other. Essentially, this meant that both parties had a profit motive for denying delays were their fault.

The first sign that the new model wasn’t the highway to heaven that the Government had sold it as came in 1997, when Railtrack was heavily criticised for failing to invest in the infrastructure which it had inherited. In 1999, two passenger trains collided near Ladbroke Grove station in London after one of the two trains passed a signal at danger, killing 31 people. The inquiry into the accident found that the training for drivers, particularly for those working for Thames Trains, was inadequate and did not account for the complicated layout of the line on the approach to Paddington. Further to this, lines on the approach to Paddington were electrified ahead of the introduction of the Heathrow Express service, which resulted in overhead power cables mounted on gantries which obscured other gantries, which carried the signals. Despite union reps repeatedly reporting sighting issues with SN109, the signal passed by the Thames Train which caused the collision, Railtrack failed to take steps to prevent the signal from being missed by drivers, despite the potentially catastrophic consequences for passing that signal at danger.

Railtrack itself was effectively nationalised just three years later as result of two more high-profile rail accidents: Hatfield and Potters Bar.

On 17th October 2000, a Great North Eastern Railway train leaving Kings Cross bound for Leeds derailed at Hatfield in Hertfordshire owing to metal-fatigue fractures in the rail, killing four people and injuring over 70. It was found that Railtrack did not keep an inventory of the state of its own infrastructure and was unaware of the state of the rail which failed at Hatfield. It was found that the rail itself had over 150 pre-existing cracks and that it had essentially disintegrated as the train passed over it. Railtrack admitted that it had allowed the engineering skills and knowledge that it had inherited from British Rail to ebb away as it divested this to contractors. As Railtrack was not aware of how many other rails within its network carried similar cracks, 1,800 separate speed restrictions were imposed while an enormous engineering exercise was undertaken to replace potentially cracked rails, causing delays and cancellations to train services across the country for months.

The Potters Bar accident happened on 10th May 2002, when the 1245 Kings Cross to Kings Lynn service derailed over a defective set of points, killing six people and leading to a bitter and ugly dispute between rail regulators, accident investigators and the contractor charged with the maintenance of the points, Jarvis. Jarvis initially claimed that the points had been sabotaged, causing them to come apart as the train ran over them and so derailing the train.

No evidence was found to support this claim and drivers had been reporting a bumpy ride over the points concerned for some time. Railtrack sent an engineer to Potters Bar to check the points, but owing to a miscommunication with the signal box, they checked the wrong points. It was found that poor maintenance of the points was responsible for causing the accident, while Jarvis continued to maintain that they were not to blame and that sabotage had to be the reason. Network Rail, which came into existence when the Government nationalised Railtrack, responded by taking all track and points maintenance in-house and ending the use of private contractors. Jarvis admitted liability for the accident in 2004.

In 2002 South Eastern, a franchise which by then had been operated by the French operator Connex for about six years, received a bail-out from the then Strategic Rail Authority of £58 million after the franchise ran into financial difficulties. Connex South Eastern became a laughing stock for everyone who didn’t actually have to use their services, with their asset-sweating of clapped out slam-door rolling stock, constant delays and cancellations of services. Despite the bail-out, Connex were stripped of the franchise the following year and services were operated by the Government for the following three years.

But the crowning example of repeated mismanagement has to be the East Coast Main Line. This line, which runs from Kings Cross in London to Leeds, York, Newcastle and Edinburgh has been vacillating between private and state ownership since 2007, when Great North Eastern Railway gave back the keys and walked away after they ran into severe financial difficulties. Just two years later, East Coast was in the news again as National Express, who had massively overbid to secure the franchise, walked away when they found that they could not turn a profit and defaulted on their payments. Having remained in public ownership for the next six years, during which it became a profitable enterprise and was the most efficient franchise in public hands, the East Coast Main Line passed into private operation again with a partnership between the Virgin Group and transport operator Stagecoach.

Three years later, the franchise had again, for the third time, passed back into the control of the Operator of Last Resort as Virgin and Stagecoach handed back the keys and sailed off into the sunset as they yet again failed to make a decent profit from the franchise and pulled the plug for good. Since 2018, the East Coast Main Line has been operated by a publicly-owned entity called London North Eastern Railway.

In 2020, Arriva, the operator of the Northern franchise, became only the second rail operator since privatisation to be stripped of their contract. With declining punctuality, industrial relations problems, staff shortages and the introduction of emergency timetables to manage them, as well as the Department of Transport calling Northern’s manifold train cancellations, particularly at weekends “unacceptable”, it was inevitable that Arriva’s tenure would come to an end. Arriva themselves blamed Network Rail among others for the issues which beset the franchise and claimed that the Department of Transport failed to lead on improvements to the infrastructure at Manchester Piccadilly station, including the building of two new ‘through’ platforms (there are only two through platforms there at present) which would have eased congestion to the north of the station.

This was all before the Covid pandemic, which ripped through the rail industry as the Government enforced brutal lockdowns on workers resulting inevitably in largely empty trains running on almost full timetables for months on end.

KeolisAmey Wales, which had been running the ‘Transport for Wales’ rail franchise since 2018, collapsed in 2021 after suffering huge losses during the pandemic, leaving the Welsh Government no alternative but to step in and nationalise it. The Scotrail franchise was ended three years early and taken back into public ownership in April 2022. Abellio, the Dutch state-owned rail operator, which had been operating the franchise since 2015, suffered severe performance issues, including many of the problems in staffing, industrial relations and delays suffered by Northern a few years earlier.

Which brings us full circle back to TransPennine Express. On top of the almost standard issues of staffing, delays and cancellations, passengers have complained of severe overcrowding, with one train from Manchester to Middlesbrough shown to be the third most crowded train in the country, with 269 passengers squeezed onto a train with a capacity of just 166. FirstGroup’s tenure will end as operator of the franchise on 28th May and services will again be provided by the Operator of Last Resort. TransPennine has also been one of 15 rail companies who have failed to give their staff a pay rise since 2019, which has seen them fall victim to industrial action on the part of ASLEF and RMT.

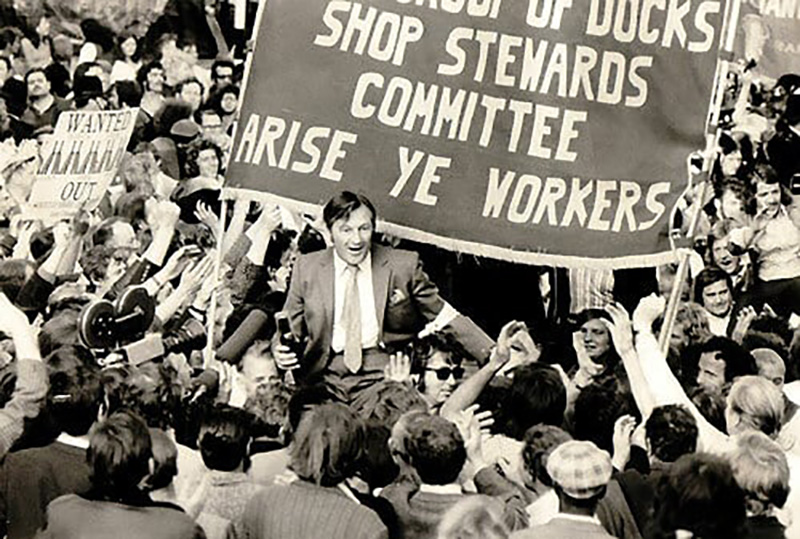

Outside of the Conservative party, it’s very difficult to find any advocates for rail privatisation. It has been a near thirty year disaster for rail passengers, though it has been largely very lucrative for those rail operators who have managed to wring a profit out of their franchises. It has also been very lucrative for some within the trade union movement – former General Secretary of train drivers’ union ASLEF, Lew Adams, spoke effusively about the benefits of privatisation, particularly for his members, who benefitted from the creation of an internal market within the rail industry for the skill of driving trains. Mr Adams managed to land himself a job on the board of Virgin Trains in 1998 after losing his post as General Secretary.

The Labour Party, which has had a largely inconsistent position on rail nationalisation for years, closed as many railway lines when in Government as the Conservatives did during the post-Beeching Report period and was as skeptical in their view of the railway in the 1960s as the Tories were, albeit for different reasons. While the Tories were keen to expand the country’s road network and were influenced by vested interests from within the road construction industry, Labour saw the motor car as the great liberator of the people and the railways as a Victorian relic. When in Government from 1997 to 2010, they opted against taking strong remedial action in the wake of the Ladbroke Grove tragedy, opting instead to mandate the introduction of the Train Protection & Warning System, a back-up safety system which was cheaper to install than the much more robust Automatic Train Protection (ATP) system. In fact, the track layout on the approach to Paddington, where the Ladbroke Grove accident happened, was designed on the premise that the signalling would be upgraded to ATP, but this was never installed.

Labour’s largely dreadful manifesto for the 2015 General Election contained the wishy-washy pledge not to nationalise the railways, even though it was a policy which had been passed at Labour’s Annual Conference, but to allow the State to bid against private companies for rail franchises. Ed Balls, the failed former Shadow Chancellor, was openly hostile to rail nationalisation, as he believed that it was prohibitively expensive, despite the State having the powers to end franchises early, as described above. Even in 2017, when Labour’s manifesto clearly stated that they would bring the railways into public ownership, behind the scenes those within the party charged with working out how to nationalise the railways were undecided on how to actually do it, with some favouring mutualising franchises, others wanting to bring back British Rail, while others leaning towards creating cooperatives to run the railways.

Regardless of which party or parties form the next Government, it looks unlikely that any of them will bite the bullet, give in to overwhelming public demand or even bow to the laws of economics and renationalise the railways any time soon. They all remain committed to capitalism and its need to open any and all public services to the opportunity to create profit. British Rail was not without its flaws, but managed over forty years to upgrade huge sections of its network, to replace its expensive and labour-intensive steam locomotives and to operate services the length and breadth of the country despite decades of indifference and outright hostility from Governments of both colours.

Unfortunately, it took the foolhardy and ideologically-driven privatisation of British Rail to teach us a near thirty year long lesson on how good it really was and why, frankly, it can’t come back too soon.

Leave a comment