On October 2nd 2001, Houston-based energy company Enron declared bankruptcy.

It was the biggest corporate failure in history and stands to this day as the biggest collapse through fraud of any company. Over 20,000 people lost their jobs and their pensions as the company imploded in scandal, disgrace and illegality. It also took one of the then ‘Big Five’ auditors, Arthur Andersen, with it. Senior figures in the company were sentenced to years behind bars for their actions. One executive, Cliff Baxter, committed suicide.

The collapse of Enron is a case study, not only in capitalism as a system and how it works, but in the manner with which capitalism twists and contorts the morality of otherwise well-intended human beings and the collective psychosis that can be created when people are driven by one single motive: Profit.

The Birth of Enron

Enron began its life in 1985 through the merger of two energy companies: Houston Natural Gas, based in Texas, and InterNorth, which was based in Omaha, Nebraska. For a short while, the merged company was called simply HNG/InterNorth, then renamed itself to Enteron but, having realised that enteron was also the name of the gastro-intestinal tract, the company hastily renamed itself again to Enron. They were headquartered in the imposing 50-floor skyscraper at 1400 Smith Street, Houston.

Pivotal in the merger of HNG and InterNorth and in the story of Enron was a man called Kenneth Lay. Lay, an unassuming Texan whose father was a preacher, grew up in a very poor family after the general store that they owned was forced to close down. Having relocated with his family to Missouri, Lay succeeded academically as well militarily, where he ascended to the rank of Lieutenant in the US Navy. His entire working life was based in the energy industry, starting at Humble Oil in the 1960s, then spending the remainder of his career within the gas sector of the industry, ascending to President of Transco before moving to Houston Natural Gas in the same role in 1984.

In 1985, he led negotiations for HNG as they were bought out by Nebraska-based energy firm InterNorth. As part of the negotiations, Lay secured the position of President of the newly-formed company, known for a short time as HNG/InterNorth, then via its naming faux-pas of Enteron before becoming Enron. From its earliest days, Kenneth Lay wanted Enron to break from being a simple gas-selling company to becoming an energy stock market company – a hub where suppliers and customers could come together to trade and Enron sweep up the commissions. It would certainly make Enron a more dynamic, diverse and profitable company, but it also came with severe risks, which later became glaringly obvious.

For the first five years of its life, Enron was focussed on the steady, if unexciting, world of selling natural gas. That was until 1990, when Enron hired a smart, driven and extremely ambitious individual called Jeff Skilling.

Skilling first popped up on the radar of Kenneth Lay in 1987, when he was a consultant for McKinsey & Company, a business consultancy firm, who were hired by Enron to assist in creating a ‘forward market’ for natural gas. A forward market is a mechanism by which the sale and price of a commodity can be agreed in advance to offer price security and predictability to both the supplier and customer. Lay, impressed with Skilling, hired him in 1990 as the chief of Enron Finance Corporation. A year or so later, Skilling became head of the newly-merged gas marketing and finance divisions.

It was during Skilling’s rise from head of Enron Capital and Trade Resources to President and Chief Operating Officer of the company that he introduced an accounting method known as ‘mark to market accounting’. This entirely legal accounting method permits a company to anticipate the profits of a project and book those profits from the moment that the project is realised, even if in reality it doesn’t make a penny. It was this shift in accounting methodology which was the foundation on which the new, dynamic and, at least for those at the very top of the company, lucrative iteration of Enron was built. It was also this step which sealed the doom of the company.

Another key player in developing Enron’s creative accounting techniques was Arthur Andersen, Enron’s auditors. For many years there has been, and continues to be, a conflict of interest between the cold hard business of auditing accounts and more creative, and profitable, field of audit consulting – advising companies on the colourful and imaginative ways in which they can record their finances to make them look wealthier, more successful and more profitable. One simple example of a colourful accounting technique is if a business buys a new premises and renovates it for its own use: Under auditing conventions, the company can book the value of the property minus the cost of the renovation and then not have to record the cost of those renovations as a separate outlay, effectively hiding these costs in the book value of the premises. At Enron, they and Arthur Andersen took this example of creative accounting to levels unseen in the history of big business.

Our final key protagonist in this story is a financier called Andy Fastow. Fastow, a Washington DC-born man with a middle-class upbringing, was hired by Jeff Skilling in 1990. Fastow came to the knowledge of Skilling through his work on the fledgling ‘asset-backed security’ instrument: The creation of a sellable asset whose value and income are underpinned by small and illiquid assets. Fastow had a shrewd and very creative financial mind, which he deployed more and more as he ascended through the ranks of Enron, but which eventually led to his sacking and, later, imprisonment.

Under the leadership of Lay, Skilling, Fastow and others, Enron embarked on a programme of diversification. They knew that supplying wholesale gas, while predictable and steady, was not capable of generating the massive profits that they craved. For that, they needed to take risks and, as all business folk will tell you, risk is reduced by diversifying. In this pursuit, they purchased a vast array of assets, including paper mills, gas pipelines, broadband, power stations and water companies. Enron purchased Britain’s Wessex Water company in 1998. Part of this diversification was to fund, manage and then run huge projects like building power stations, including the now infamous Dabhol power plant in India.

Dabhol

In the pursuit of super-profits, countries like India were often avoided as a matter of course by western capitalists. For them, there were too many governmental layers, too much red tape and, to be blunt, too much poverty in India to give any company from distant climes the opportunity to make much money. Enron intended to break that pattern and show that they, the great financial and business innovator that they thought they were, could go to India, make a major investment and make a profit. Their $2bn Dabhol venture was based in Maharashtra State, just south of Mumbai on the west coast of India.

Enron commenced construction of the Dabhol power plant in 1992. It was to be commissioned in two stages – the first stage was a 740 megawatt facility, while the second stage would total an output of 1,700mw when it was commissioned. The contract that Enron sealed with the publicly-owned Maharashtra State Electricity Board was never seen by local politicians and was shrouded in secrecy. Just a year after construction started, it fell into trouble, with the local electricity board trying to back out of the contract it agreed with Enron, as it would lose money on every single megawatt of electricity that the plant produced. The issues which beset the plant almost from the start became a topic of debate in the local political sphere, with the local Bhartiya Janata Party-Shiv Sena coalition being swept to power in its local legislature elections in 1995 on a pledge to “push Enron into the Arabian Sea”.

With the dispute between Enron and the electricity board reaching an apex in 1995, they halted construction at the plant, which at the time employed some 15,000 construction workers. The contract between the board and Enron was subsequently renegotiated in order to allow construction to restart, which included a cut in the wholesale price of electricity which Enron would sell to the electricity board, but pushed up the amount of electricity that the board would be obliged to purchase.

The plant commenced operation in 1999, with the electricity board paying Enron two and a half times the amount it was charging Maharashtra’s users for the electricity the plant was generating. Meanwhile, Enron booked the profits that it predicted it would make on the plant on its accounts, while the aftershocks of the project, its costs and the amount of money it fleeced from the electricity board is still being felt in India, where as recently as last year there were calls for a judicial review of the whole project, the contract made between Enron and the electricity board and the rampant corruption, kickbacks and back-handers which brought the scheme into being in the first place.

Blockbuster

Another example of Enron’s willingness to take risks and book huge and imaginary profits was an ambitious partnership it forged with the now-defunct video hire company Blockbuster. Under the deal, Enron Broadband Services, a sub-division of Enron, would stream films and TV programmes supplied to it by Blockbuster into the homes of millions of Americans. It was to be what Netflix eventually became: A service which beamed film and television content on demand to subscribers via the internet. However, Netflix launched its streaming service in 2007, when broadband internet technology had advanced to a stage where it could make such a service viable. Enron made this deal with Blockbuster in the year 2000.

The deal with Blockbuster was made at a time when broadband technology was still in its infancy. The internet was growing into the worldwide phenomenon it was destined to be, but wasn’t there yet, and many computers connected to the web still used ‘dial-up’ connections, which were slow and, critically, did not have the bandwidth to support the streaming of content at the quality that Enron and Blockbuster needed to make the service attractive to customers. Enron sought to use the deal and the promise of instant-access video as a catalyst to roll out full broadband to cities across the United States.

Wall Street bet almost everything on the burgeoning internet phenomenon and hundreds of new companies began to pop up, hoping to get their slice of what was becoming and extremely large and lucrative pie. Then came the bursting of what became known as the ‘dot-com bubble’: Billions of dollars was wiped from the book-value of these start-ups, whose value was already massively over-inflated, and many companies collapsed completely. It was at this time that Enron decided to go headlong into a huge project to upgrade internet connections, costing it hundreds of millions of dollars. The upgrades yielded almost nothing in actual returns for Enron, yet Enron booked the profits that it believed it would make on a streaming service it had abandoned after eight months and on broadband services that hadn’t made an actual penny.

Skilling was at the vanguard of booking these imagined riches in the company’s accounts and, to a large degree, used this fictitious capital to mask the heavy losses that Enron was really making, not only on the failed joint venture with Blockbuster, but in the money pit that the Dabhol power station project had become.

How Does Enron Make Its Money?

Enron’s share price rose exponentially between 1990 and 1998. A culture was nurtured at Enron where the price of its shares was the be all and end all: Enron’s share price would be emblazoned on the walls of its offices and even on a dot-matrix display inside all the lifts of its head office. Executives would use the phrase ‘pump and dump’ to describe their ethos – they would encourage their subordinates to do everything within their power to push the Enron share price higher and higher, while they would cash in their generous share options and add to their ever-increasing fortunes. By 2000, the share price of Enron has reached an all-time high – $90.56, which valued the entire company at around $65bn.

But questions were beginning to be asked about the company and, crucially, how it actually made its money. On its face, this should be a fairly straightforward question for anyone engaged at the senior level of a major corporation to answer: Ask an executive at Ford Motor Company how they make their money, they’d say that they make and sell cars. Ask an executive at Marks & Spencer how they make their money, they’ll probably answer that they sell clothes and food. Yet the question of how Enron made its money was one which was apparently so difficult for its senior officers to answer, it unwittingly became a gentle tug on a thread which was to eventually unravel the whole company.

Bethany McLean, a journalist for Fortune magazine, asked this very simple question. She was curious as to how a company that had a diverse portfolio of interests but ostensibly dealt in energy could have the trailing price-to-earnings ratio that it had. This ratio is calculated by taking the current stock price and dividing it by the trailing earnings per share for the previous 12 months. In the case of Enron, the price-to-earnings ratio was 55:1, which was an absurd figure on its face and even more absurd given the businesses that Enron was in and the ratios of its energy-sector competitors.

Enron also shrouded its finances in secrecy and, when it did share its numbers, they were often compiled in a way that made them almost completely incomprehensible. Wall Street analysts knew that Enron was worth a fortune and was, at least on its face, a successful company, but no-one could quite put their finger on exactly why. Critically, as long as Enron’s share price continued to soar and for as long as the company’s accounts showed that they were a roaring success, they didn’t really care, either.

Some of the techniques that the company used to hide losses and debts, as well as book income that even didn’t exist was decidedly unsubtle: For instance, Enron, through an entity it created, sold three power barges (essentially ships with electricity generators on them) based in Nigeria to investment bank Merrill Lynch, who had absolutely no need or use for them, only to buy them back from the bank six month later and book $12m in profits.

The Special Purpose Entity

Jeff Skilling’s ‘Mark to Market accounting’ was key to Enron being able to hide its losses and debts through over-booking profits imagined from major projects. But Andy Fastow, Chief Finance Officer of Enron, developed a scheme using what are known as ‘Special Purpose Vehicles’ (SPVs) or ‘Special Purpose Entities’ (SPEs): Off-book financial instruments which would be used to hide Enron’s losses and/or debts from the main audited accounts of the company.

The scheme would operate as follows: Enron would transfer a portion of its stock to one of its SPEs in exchange for cash or a note. The SPE would then use the stock to hedge an asset listed on Enron’s balance sheet. At the same time, Enron would guarantee the SPE’s value to alleviate apparent counter-party risk. SPEs are in and of themselves entirely legal, however the way in which Enron’s SPEs were built placed huge risks on them. The first key weakness was that these SPEs were funded entirely with Enron’s own money, based on the belief that Enron’s share price would continue to rise in perpetuity. However, if the share price of the company fell, it would severely restrict the SPE’s ability to hedge any of Enron’s assets.

The second weakness was that, while there was a glaring conflict of interest between the SPEs being used to protect the company being bankrolled by the very same company, Enron disclosed the existence of these SPEs but never revealed to investors the massive risks that they were opening themselves up to by using their own money to fund them. Fastow, as Chief Financial Officer, was also in a conflict of interest of his own as he had a foot in the camp that paid to set up the SPE and the one which hedged the same company’s assets.

They were also taking a huge risk if the Enron share price fell. It is also fair to suggest that many of Enron’s investors did not fully understand how these SPEs worked, so any red flags that there may have been would have been missed.

Fastow himself received sizeable ‘consultancy’ fees for his work in setting up and managing these SPEs – from LJM, the SPE named after his wife and children (Lea, Jeffrey and Matthew), Fastow netted $45 million.

2001

The furore caused by Bethany McLean’s article, as well as prophecies of impending doom made by noted short-sellers including Jim Chanos, meant that Enron’s share price in 2001 plunged into freefall.

Kenneth Lay, CEO and essentially the father of the company, retired in February of 2001, handing the reigns to Jeff Skilling. As the share price continued to slump, Skilling and others in the company blamed the short sellers – they, Skilling claimed, were the ones who were speaking negatively about the company and causing investors to ditch their stakes and run. Skilling’s own mental and physical health began to deteriorate as he saw not only that the cracks were beginning to appear in the Enron facade, but that other people were starting to notice it, too.

On April 17th 2001, Jeff Skilling took questions from market analysts on a conference call. One analyst made the point that Enron was “the only financial institution that can’t produce a balance sheet or cash flow statement with their earnings”. Skilling laughed, saying “Thank you very much. We appreciate it… asshole”.

As the share price fell, so more and more investors cashed out and there was nothing that Skilling or his cohorts could do to stop it. With the share price falling, the SPEs which were burying Enron’s debts and losses became exposed, meaning that, as they guaranteed them, they were on the hook for their huge losses.

Faced with what was becoming a tidal wave heading straight for the company, Skilling suddenly resigned in August 2001, citing ‘personal reasons’. Kenneth Lay, who had retired just six months earlier, returned as President and CEO with a simple mission: To save the company. While Lay, in a speech to his employees following his appointment, proclaimed that Enron would be able to turn the dire situation around, his staff were not so convinced – in a Q&A session following his speech, one employee asked Lay if he was on crack and, if not, if he had considered starting, given the company’s plight.

Enron began to take actions which attracted the attention of Securities and Exchange Commission, the agency of the US Federal Government set up after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 to monitor and ‘police’ the actions of capitalist entities within the US. The first was the closure of the ‘Raptor’ SPE, while the second was to announce that it had made its first quarterly loss, while finally was the decision to change the administrators of Enron’s pension fund and forbade its members from selling their Enron shares for a period of thirty days.

The SEC announced that they were investigating Enron, specifically the SPEs that they had set up. Enron responded by sacking Andy Fastow. The company then went into a process of ‘full disclosure’, re-stating their earnings and, crucially, their losses going back to 1997. It was revealed that, by 2001, the company had losses of $591 million and debts of $690 million. A vaunted merger with a company called Dynegy, which would have save the company at least to some degree, collapsed when Dynegy pulled out, citing a “material adverse change” in Enron’s business status, which arguably was the comparatively smaller company looking at the state of the larger one it was looking to merge with and believing that Enron’s liabilities would take Dynegy down with it.

It was this which cast the die for Enron. Four days after Dynegy binned their merger, Enron filed for bankruptcy.

Charges

The SEC moved to charge Enron’s key officials. Andy Fastow, who was sacked by Enron in an apparent act of self-preservation, pleaded guilty to two charges of Wire Fraud and served five years in prison by cutting a deal with prosecutors to inform on the actions of his cohorts. Kenneth Lay was charged and found guilty on six counts of counts of fraud and conspiracy and four counts of bank fraud, He died of a heart attack before he could be sentenced and his conviction was vacated.

Jeff Skilling, the man who helped turn Enron into what it was, was convicted of conspiracy, insider trading and fraud and was sentenced to 17½ years in prison, which was subsequently reduced to 14 years. Skilling was also required to pay $42 million dollars in reparations to the victims of the fraud perpetrated at Enron.

Arthur Andersen, the auditors which aided and abetted Enron in their huge and unbridled fraud and attempted to hide their complicity by shredding a ton of Enron paperwork, were convicted by the SEC of attempting to obstruct justice, but this conviction as overturned by the Supreme Court. However, as the reputation of the company was in as many pieces as the documents they had shredded, they dwindled out of existence as an entity and subsequently became Andersen Global having been bought out.

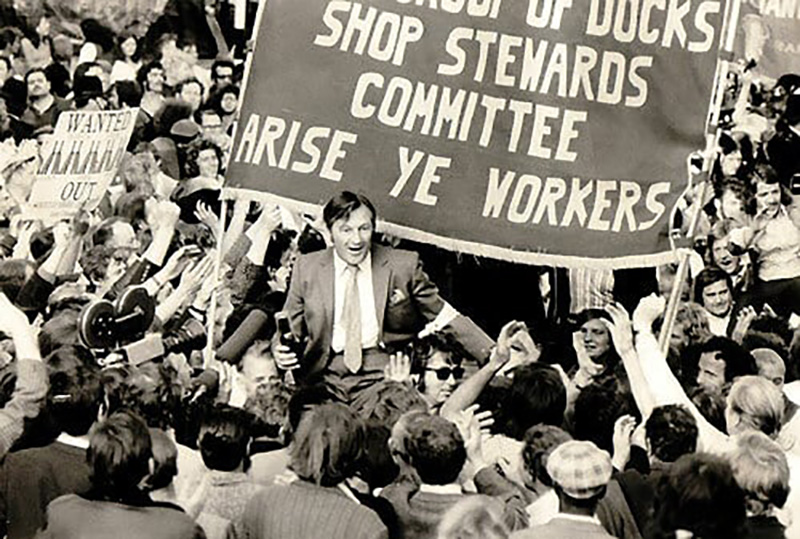

The Workers

The biggest victim of the Enron scandal were the workers at Enron. For years, they had been encouraged to buy Enron stock to put into their ‘401k’ – a retirement savings plan which workers use to create a nest-egg for their retirement whilst taking certain tax advantages. Enron’s higher-ups, proclaiming that the seemingly never-ending rise of the share price of the company would give their workers a comfortable retirement, never told them that they themselves were cashing out when the writing was on the wall for the company and then forbad them from cashing out themselves for a full month when the share price began to fall through the floor.

People who began their careers at companies that were bought out by Enron, including electricity companies like Portland General Electric, found themselves with investment portfolios that were almost worthless – some lost hundreds of thousands of dollars which they never got back.

The US Government, seeing that the scandal at Enron would severely dent confidence in the system, sought to compensate investors in the company in preference to the workers whose pensions went up in smoke. They settled with investors for $4.2 billion, while the workers received just $85 million. It required a class-action lawsuit on the part of the affected workers to reclaim what originally was $356 million, but, scandalously, this was reduced on appeal to a measly $37.5 million.

Could there be another Enron?

A raft of new laws were introduced following Enron’s collapse with the intention of preventing a similar scandal happening again. It is debatable whether any legislation would prevent any group of like-minded individuals from carrying out anything quite like what Lay, Skilling and Fastow managed to get away with for years at Enron. In this country, Carillion, a construction and facilities company born out of a de-merger of Tarmac, collapsed in 2018 after years of exorbitant executive pay and false auditing which echoed the rise and fall of Enron, demonstrating that the lessons from the United States were not learned here.

Capitalism has scandals like that at Enron and Carillion, as well as hundreds of others, hard-wired into it: It is tacitly accepted that, in the pursuit of profit, ‘bad actors’ will take advantage and sink major companies and, frankly, that is something that capitalism is happy to deal with, despite its claims to the contrary. But it is the workers, without whom none of these companies could turn a profit, who are always the hapless and blameless victims of capitalism’s bankrupt culture.

Leave a comment