It is over thirty years since a young and fresh-faced John Part from Canada thrashed Bobby George 6-0 in the final of the 1994 World Darts Championship, organised by the sport’s governing body in this country, the British Darts Organisation. John, 28 years old at the time, overcame the huge crowd favourite George, who became a finalist of the world championship for the first time since 1980. But this was no ordinary tournament. It was the first BDO-organised tournament since what was one of the most bitter and seismic splits in British sporting history.

The split had its roots many years before 1994. In fact, it could be argued that it was as far back as 1980, with a sketch on the comedy show ‘Not the Nine O’Clock News’, featuring two hugely obese men (played by Mel Smith and Griff Rhys-Jones with heavy padding around their waists) competitively swilling beer and spirits, all with commentary by Rowan Atkinson, effecting a Geordie accent. The sketch was a parody of professional televised darts – Atkinson’s Geordie accent was in reference to Sid Waddell, who commentated on the BBC’s darts coverage, while the heavy-drinking protagonists were an amalgam of a number of portly and heavy-drinking darts players of the time, including Leighton Rees and Jocky Wilson.

While there is a case to be made that a comedy sketch broadcast in 1980 is unlikely to be the causal link to the antagonisms within professional darts bursting open some thirteen years later, it is certainly the case that, in the eyes of the public, the sketch parodied – possibly even mirrored – what televised darts in the early 80s was really like: Heavy-set men drinking alcohol and smoking on stage while they plied their working class trade of throwing darts at a board for money.

While there is a debate to be had whether darts is a sport at all (and it is, by the way), darts has always been hugely popular in Britain. It is very rare to see a dartboard in a pub or social club without at least a couple of people playing a game on it and, as five-time world champion Eric Bristow once said, the nation’s affinity with darts comes from the fact that virtually everyone has thrown a dart at least once in their lives. With the post-Great War period marked by pressure from both the Government and the Temperance Movement to persuade working class people to do more than just go to the pub and get drunk, breweries and pubs acceded to their demands and introduced amusements like dominoes, bagatelle, bar billiards and darts.

The game of darts at that time was played according to differing standards and even differing dartboards (for instance the Yorkshire dartboard had no trebles or outer bull), it was clear that standardisation and formalisation of the game would be required if it was to flourish nationally. In 1925, the National Darts Association of Great Britain was formed with a number of key aims: The first being to unify the sport around a standard board, to sanction competitions and, in the spirit of keeping the working class from harmful pursuits, to suppress all forms of gambling. They also set up a county-based structure for tournaments, a structure which still exists today.

With pubs doubling as both a meeting place and a venue for darts matches, tournament darts became huge in Britain – be they friendly (or at least semi-friendly) matches between pubs, to formal leagues and open tournaments, all the way through to the News of the World championship, which was established in 1927 and invited players representing their local pub to compete in a simple best-of-three leg format which stayed consistent from the first round all the way through to the final. The tournament was also notable for setting the throwing distance at eight feet, where the then more standard throwing distance is 7 feet 9¼ inches. From 1963 to 1977, the finals would take place in the Great Hall at Alexandra Palace in front of crowds of some 17,000 people, with the coverage being televised in its later years.

Darts’ big break in terms of transforming it from a pub-based pastime to a televised sport from which players could actually earn a living was Indoor League, a programme devised by Sid Waddell (who later went on to become darts’ most famous commentator) which was broadcast on Yorkshire Television from 1973 to 1977, hosted by the cricketer Fred Trueman. Trueman would open the programme wearing a cardigan, with a pint in one hand and a smoking pipe in other, as competitors battled out over games including bar billiards, arm wrestling, pool and darts. The darts tournament was initially restricted to players from only the Yorkshire TV region, but in later series expanded to nationwide tournaments as the popularity of the competition, and the programme, grew.

The technology available in the early 1970s meant that the darts tournaments would be broadcast using a two camera set-up: One camera would take a wide shot of the player and the board, while a second camera was focussed solely on the board, zooming in as and when required, with the two cameras alternating as directed. It was a far-cry from the split-screen, graphics-laden style of coverage we see today. Commentary came from Dave Lanning, who became a noted darts commentator for ITV and Sky in later years. Winners of these televised darts tournaments included Leighton Rees, who became the first World Darts Champion in 1978.

Running parallel to this unprecedented coverage for what was, until then, a pub-based pastime, was the further formalisation and standardisation of the game with the founding of the British Darts Organisation in 1973 by a Muswell Hill-based Londoner and businessman called Olly Croft. Croft, who took up the game in 1961 and made his living founding a tiling company, formed the BDO at an inaugural meeting in Muswell Hill on 7th January 1973. In effect, this was the original split in darts – the National Darts Association had already established an inter-country amateur darts structure, but did not organise national tournaments. Croft believed that the future of the game lay in both a strong county-base structure, but also in national and international tournaments, so decided to set up a rival organisation to the NDA in the BDO. The World Masters (often known as the Winmau World Masters thanks to its long-term sponsorship by the darts and dartboard manufacturer Winmau) became the first national tournament, founded in 1974.

A pivotal moment in the televised coverage of darts came when two camera shots could be shown simultaneously on screen. This meant that the two camera set-up we described above in the Indoor League could be shown on screen at the same time, so one camera could focus on the player throwing, while another would be trained solely on the dartboard, meaning that the viewer at home would not miss a thing. From this was developed the now staple zoom-in shot when the player hit the treble 20 with their first two darts, with the camera fixed on the segment to confirm whether or not the player hit a 180, which is the maximum three dart score.

Darts expanded exponentially in the 1970s at pub, county and national levels, as well as a televised sport in its own right. The World Darts Federation was formed in 1974, mainly through the efforts of Olly Croft, and the BDO established further tournaments including the World Darts Championship, which held its inaugural tournament in 1978 in Nottingham. This inaugural tournament was the first and only World Championship to be played in ‘matchplay’ format rather than ‘set play’, and Leighton Rees overcame John Lowe 11-7 in the final. Lowe was to take his revenge the following year, defeating Rees in the final by five sets to nil, but a man who was knocked out at the quarter-final stage of the 1979 tournament was set to dominate the game and launch darts into the stratosphere.

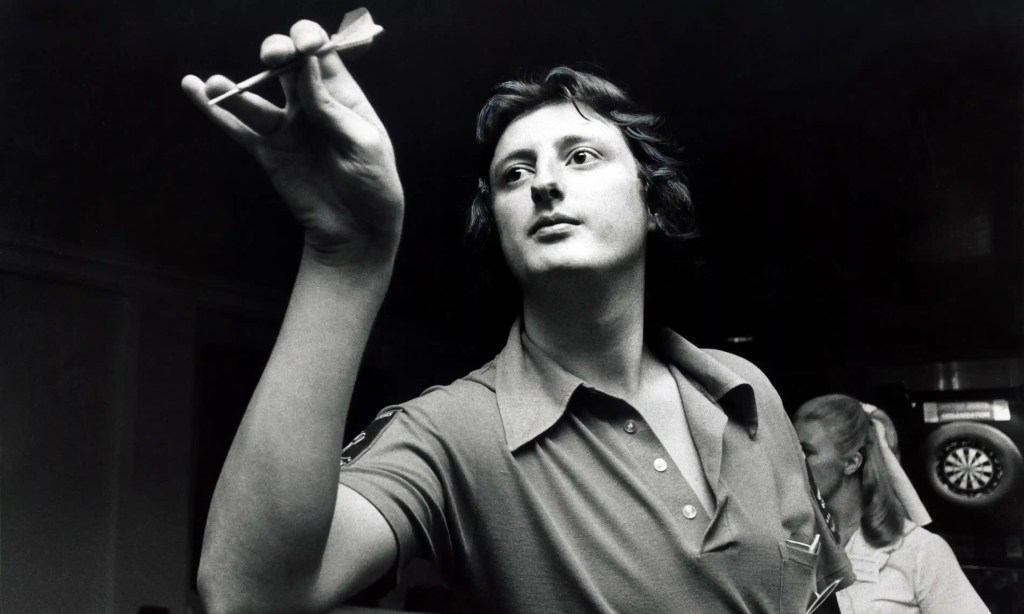

Eric John Bristow, a young, brash, arrogant and incredibly talented darts player from Stoke Newington in London, won the World Championship in 1980, aged just 22, by beating Bobby George in the final. Bristow went on to become the most successful darts player of the era and one of a number of instantly-recognisable faces of top darts players alongside Jocky Wilson and John Lowe. It was Bristow’s dominance of the game – he went on to win the World Championship five times and was a finalist ten times – and the popularity of the darts-based game show ‘Bullseye’ which began airing in 1981, which created a sport where working class men could graduate from winning darts matches in their local pubs to winning thousands of pounds playing darts for a living.

Both BBC and ITV, the only television broadcasters at the time, covered darts extensively in the early 1980s, either by showing darts live or by broadcasting pre-recorded packages on programmes like Grandstand (BBC) or World of Sport (ITV). The prize money grew exponentially as sponsors clambered to adorn their name on these televised tournaments and in 1982, John Lowe won the biggest cash prize in darts when he completed the first televised 9-darter. A 9-darter is the ‘perfect game’ – the minimum number of darts required to complete a 501 leg of darts with a double finish. Lowe completed the feat at the MFI World Matchplay in Slough in Berkshire when playing against Keith Deller and pocketed £100,000 in the process, and astonishing amount of money at the time and, as he said in his autobiography, a life-changing win which paid off his mortgage and gave him long-term financial security.

It seemed that the darts bubble would never burst – Jocky Wilson was being interviewed by Terry Wogan and appeared, or at least a picture of him appeared, on Top of the Pops, professional players were on television every Sunday evening on Bullseye and both main broadcasters couldn’t broadcast enough tournaments. But the bubble did burst, and it was this bursting of the biggest and most lucrative of bubbles which led to the acrimonious split in darts.

Darts tournaments were broadcast at a breakneck pace and it was difficult for the casual viewer to discern which tournament they were watching from one week to the next. One key reason for this was the formats that the tournaments were played in – the BDO sanctioned their televised darts competitions in standard set play format, 501 legs with a double finish, which meant that every tournament appeared to be similar, except for the venues that they were played in. The broadcasters were also beginning to become averse to constantly broadcasting men smoking and drinking on stage, particularly given that the bulk of the televised coverage was broadcast on weekend afternoons and impressionable children could be watching.

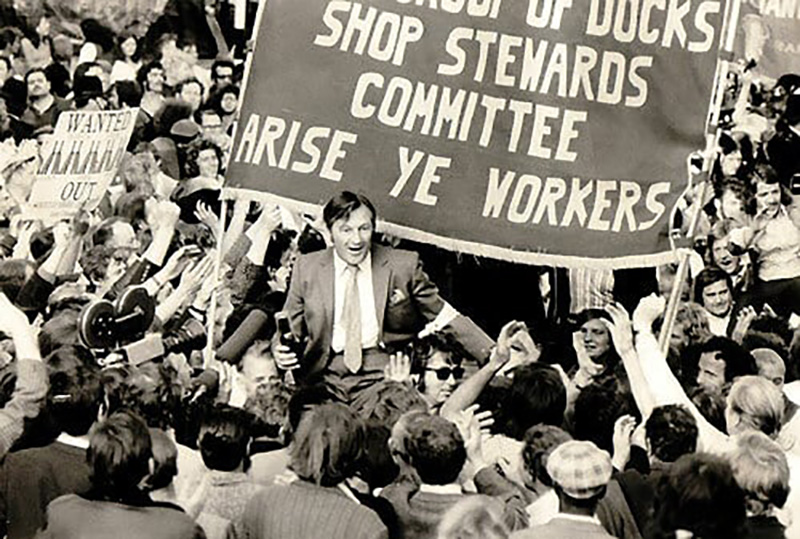

It should also be considered that the period from 1984 to 1988, where darts coverage in the decade peaked and then tailed off considerably, was a particularly tumultuous one in wider society – the Miners’ Strike took place from 1984-85, to be followed by the printers strike in 1986: Both bitter and prolonged disputes where the working class went headlong into conflict with the ruling class and the splits within the working class and the trade union movement were cruelly exposed. Alongside this, the ever-present phenomenon of football hooliganism burst open in most violent fashion during this period: In 1985, Millwall and Luton fans were involved in violence at Luton Town’s ground, Kenilworth Road before, during and after an FA Cup sixth round match, in arguably one of the worst episodes of British football hooliganism of the period. In the same year, 39 fans were killed at the Heysel Stadium disaster when clashes between Liverpool and Juventus fans led to a wall collapse at the Belgian venue of the European Cup Final. English football clubs were banned from European competitions for five years as result.

These and other events created a deeply and overtly anti-working class stance in the ruling class, and this manifested itself in the reporting, broadcasting and commentating through the bourgeois media of the time. To the ruling class the working class, particularly the male half of it, were boorish, work shy, drunken and violent louts who needed to be beaten into submission by the police, penned-in behind electric wire at football grounds and made to carry identity cards to watch a football match. The notion of broadcasting working class men earning thousands of pounds to swill beer, smoke fags and throw darts became intolerable to BBC and ITV and their ruling class-adjacent commissioners.

The rot in terms of televised darts coverage began in 1984, but by 1988, the year when the BDO banned smoking on stage, to be closely followed by the ban on on-stage drinking, there was one solitary tournament still being broadcast in television – the Embassy World Darts Championship. Former televised tournaments were either curtailed or cancelled completely as sponsors abandoned the sport, meaning that professional players had less and less opportunities to ply their trade and earn a living. The British Darts Organisation and Olly Croft did little to address the situation – their focus was always on maintaining the amateur side of the sport on the premise that looking after the pennies meant that the pounds – the televised tournaments – would look after themselves.

However, the boom in televised darts in the first half of the 1980s created a strata of players who earned a living from the game. They were no longer amateurs, they were professionals, and the organisation whose tournaments they earned a living from were steadfast in their view that they did not owe a small layer of darts players a living and their obligation was to the amateur side of the game. This situation perpetuated into the early 1990s, when the world’s top 16 players came together to demand concessions from. the sport’s governing body.

The players formed their own professional body, the World Darts Council, and even wore WDC logos on the arms of their shirts at the 1993 World Championships before BDO officials demanded that they remove them. During this tournament, they put to Olly Croft that they needed televised tournaments to earn a living and, according to Eric Bristow, who negotiated with Croft on behalf of the rebel players, the conversation went in this fashion:

Bristow: “Can you guarantee us more than one televised tournament per year?”

Croft: “No.”

Bristow: “In that case, would you mind the top players organising their own televised tournaments?”

Croft: “Yes I would.”

Bristow: “And what would happen to players who organised their own tournaments?”

Croft: “They would be banned”

This brought the sixteen top players in the BDO to breaking point. They had been forced to remove their WDC logos in humiliating fashion and their genuine concerns about the future of the sport were ignored. Shortly following the 1993 BDO World Championship, the sixteen players wrote to the sports governing body and stated that they would not compete in the 1994 World Championship unless it was under the auspices of the WDC – effectively creating two separate governing bodies for the sport: One for the top professional players and the other for everyone else. But the BDO would not tolerate a rival organisation, and so on 24th January banned all sixteen players from playing in any BDO-sanctioned tournaments. But they went even further – they barred any BDO-affiliated member from taking part in any event in which a WDC player was a participant, even exhibition events.

In April 1993, that ban was extended worldwide through the World Darts Federation, which Olly Croft affiliated the BDO to when it was founded, held an extraordinary meeting in Las Vegas. The sixteen players were officially excommunicated from the British and the world game, and resorted to playing tournaments within themselves. Their inaugural televised tournament post-split was the 1993 Lada UK Masters, which was organised under the auspices of the WDC and broadcast by Anglia Television. The tournament, which was played under the rarely seen on television ‘equal darts’ rule, was won by Mike Gregory, who controversially reversed his decision to split from the BDO and rejoined the organisation a few weeks later.

The players took advantage of the launch of Sky Television to launch their own world championship. The WDF would choose the Circus Tavern in Purfleet in Essex as the venue for the 1994 WDC World Championship, which included the now fourteen remaining rebels (Chris Johns had also decided to return to the BDO) and a number of invited players from Britain and the United States. The tournament was so poorly attended that WDC officials would corral passers-by into attending for free. The winner of the first WDC World Championship was Dennis Priestly, who beat Phil Taylor by 6 sets to 1 in the final.

A bitter and expensive legal dispute between the two organisations began. The players of the WDC claimed that the ban that the BDO and WDF had imposed on them was a restriction in trade. After years of wrangling and some £300,000 in legal fees spent, the two sides negotiated a settlement in form of a Tomlin Order in 1997: The BDO recognised the WDC as a governing body of the sport of darts (although the word ‘World’ had to be removed from the name of the players’ organisation, which became the Professional Darts Corporation), while the case against the BDO for restriction in trade and consequential damages caused was dropped. There would be two rival organisations of the sport of darts – the BDO and PDC.

The two organisations co-existed alongside each other for the next nine years. The PDC, while smaller in terms of the number of active players, could offer greater prize money thanks to its association with Sky and other sponsorship deals. It also had Phil Taylor, who dominated the PDC World Championship between 1995 and 2006, winning the tournament eleven times in this period. However, the greater strength in depth remained in the BDO – while there had been a number of players who ‘defected’ from the BDO to the PDC, the bulk of professional darts players stayed with the BDO. Indeed, it could be argued that the best darts player in the world in 2000 was not Phil Taylor, but Ted Hankey, who won the BDO World Championship by thrashing Ronnie Baxter 7-0 in sets in the final.

The balance of power between the PDC and BDO tipped in the favour of the PDC in 2006, when the Netherlands’ Raymond Van Barneveld, the then four-time BDO World Champion, switched from the BDO to the PDC. Barneveld was the world number one at the time he switched and it was a seismic event in the sport of darts. Barneveld was placed straight into the Premier League Darts tournament which took place over a number of weeks playing in assorted venues around the country. Barneveld was knocked out at the semi-final stage, but, having thrown a nine-darter in Bournemouth in March 2006, darts fans sensed that a player that could truly rival Phil Taylor had arrived in the PDC.

The two players clashed in the UK Open in Bolton at the quarter-final stage. Barneveld overcame Taylor in the deciding leg of the best-of-21 leg match, taking out 97 with two darts when Taylor missed his chance to snatch the match. Barneveld went on to win the tournament. But it was the 2007 World Championship which arguably set the PDC above the BDO. Barneveld faced Taylor in the final and what followed what an epic, three-hour, thirteen set classic, which Barneveld won in a sudden death leg. It capped off a tremendous year for Barneveld and sparked a growth in the PDC which would lead to the steady decline of the BDO.

The PDC switched the venue for the World Championship from the Circus Tavern, which held barely 800 people when set up for darts crowds, to Alexandra Palace, which held 2,500 fans and was a return to the ‘home’ of darts, being the venue of the News of the World Championship for many years. One also has to wonder whether it was the PDC cocking a snook at Olly Croft, the head of the BDO, whose office was only down the road from the imposing Palace. Prize money continued to grow in PDC tournaments and players continued to make the leap from the bosom of the BDO to the potential riches offered by the PDC. For darts fans, this was a mixed blessing – to see the best players in the world in the same darting organisation was a dream come true, but with the increase in prize money came the inevitable rise of ticket prices for fans who were, in the main, working class people. It also meant that small but atmospheric venues like the Circus Tavern were jettisoned for cavernous places like the O2 in London. Working class fans were being priced out of their sport.

For the BDO, they continued as they had always done – managing the amateur side of the sport and letting the professional side look after itself. Some players, including Eric Bristow, said that they thought that Olly Croft believed that he owned the sport of darts. As more and more top players left to join the PDC and with political turmoil at the highest levels of the BDO, Croft found himself voted from the board of the organisation that he founded. With sponsorship from tobacco firms banned, the Embassy World Darts Championship became simply the World Darts Championship, becoming sponsored by the very venue that the tournament took place at – the Lakeside in Grimley Green Surrey.

The BDO’s demise was sealed in 2020. Having controversially moved the venue for the World Darts Championship from the Lakeside to the O2, a number of players withdrew from the tournament when the organisers appeared uncertain about what the prize fund for the tournament was. Ticket sales were lacklustre throughout the event and many sessions were broadcast live on television with swathes of seats empty. Indeed, the two finalists, Wayne Warren and Jim Williams, had no idea how much money they would win when they played their match. In the end, Warren, who became the oldest BDO World Champion at the age of 57, won £23,000 for his week’s work: Peter Wright, who won the 2020 PDC World Championship a few miles away in north London, picked up a prize of £500,000.

The British Darts Organisation collapsed into bankruptcy in September 2020. What remaining players there were in the organisation migrated to the PDC, with the World Darts Federation stepping in to organise the World Championship, which was reconstituted in 2022.

Leave a comment