The last executions in Britain were those of Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans, who were hanged simultaneously in Walton and Strangeways on 13th August 1964. They were sentenced to death after attempting to rob a laundry van in Cumbria, which culminated in the beating and stabbing to death of the driver, Alan West. A year later, Parliament passed the Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act. This suspended any further executions for five years, becoming permanent in 1969. The death penalty was subsequently removed from British law, except for military offenses, which were never lawfully used, before being abolished entirely in 1999.

The death penalty had already been contested for years, and in 1957 the Homicide Act was passed, dividing offenses into categories of non-capital and capital murder. The capital offenses included:

- Murder in the course of theft or robbery (e.g., killing someone during a burglary).

- Murder by shooting or explosion (e.g., using a firearm or bomb).

- Murder of a police officer or prison officer in the line of duty.

- Murder committed while resisting arrest or escaping custody.

- Multiple murders committed in the same act or as part of a plan.

Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans fell into the first category—murder in the course of theft or robbery. Had they killed Alan West in a fit of rage, they might have avoided the hangman’s noose, but the element of theft ultimately sealed their fate.

Recently, the death penalty has resurfaced in media and public discourse following the murders, and attempted murders, of young children at the Southport children’s party. The perpetrator, Axel Rudakubana, was born in Cardiff to Rwandan parents who moved to Southport in 2013.

The details of this event are so toe-curlingly horrifying, particularly because such young children were killed, that discussions about reinstating the death penalty are not unwarranted. There is an argument to be made regarding his mental health and the failures of local social services to address his condition. However, this article is not about the parameters of this case, but about capital punishment itself.

Britain has a long history with capital punishment, even more so—and more viciously—in its colonies. Like all laws, it has historically been used as a means of controlling the working class, or serfs before them. Knowing that the state has the power to execute people who break laws set by the ruling class acts as a deterrent, but primarily for the workers rather than those in power.

It was during the reign of Henry II (1154–1189) that capital punishment was officially codified into common law, solidifying executions as a punitive measure.

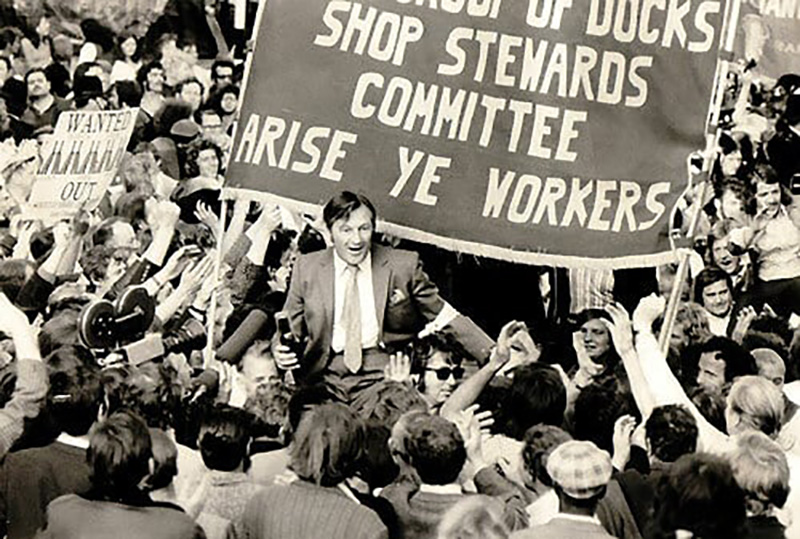

Following the growth of capitalism in British society and the increasing influence of the bourgeoisie in governance, capital punishment took a drastic turn. By the end of the 18th century there was a sharp increase in crimes deemed as capital offenses. This was to become known as the Bloody Code. Under this legal system, there were over 200 offenses punishable by death, including minor crimes such as theft of goods worth more than one shilling or poaching game from private lands. Much like the Poor Laws of previous centuries, these harsh laws specifically targeted the working class. The Poor Laws forced workers into new industries, while the Bloody Code created a legal framework to strengthen the ruling class’s grip on society and protect private property. The fact that a starving man could be hanged for stealing a pheasant may seem barbaric to our modern liberal society, but the ruling class at the time deemed such draconian measures necessary to suppress growing class consciousness and maintain control. Normalising this type of state violence by holding public hangings where people could cheer or jeer at the deaths of their class compatriots.

As industrial Britain grew the contradictions of capitalism—workers demanding more while the ruling class requires them to have less in order to increase profit—became increasingly apparent. By forcing people into industrial labour, capitalism unintentionally created a unified working class which numbered more then their ruling class and they were becoming increasingly proficient with tools, weapons and with an increasing education. The ruling elite realised that they needed to tighten their grip, using severe punishments as a deterrent against rebellion and resistance.

“The law does nothing to prevent this state of things; on the contrary, it upholds it, and if a poor devil gets into trouble, loses his job, commits a theft out of sheer necessity, the law is pitiless and grinds him down. The law is a one-sided affair. It protects the rich and powerful, but it has no mercy for the poor and weak.”

— Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England.

While this may seem unrelated to the Southport murderer, it is not. There is no debate that this man’s acts were appalling and that he should be punished—perhaps even put to death. The issue, however, is who is granted the power to execute and how they choose to wield it. Most people today understand that the state does not operate in the interests of the working class. Why should this be any different?

The state and legal system are instruments of class rule, designed to protect the interests of the ruling class and their property. They are tools of control, ensuring the preservation of the current order.

The state’s monopoly on violence already places workers in a stranglehold, and reintroducing the death penalty would only amplify this power. Framing executions as a form of justice legitimises state violence, providing yet another tool for oppressing the working class. Whether used to intimidate or eliminate, it grants the state the ultimate authority over life and death.

In conclusion, placing the death penalty in the hands of the ruling class is a dangerous precedent that would be used against us. While certain crimes and individuals may seem deserving of such punishment, we must not arm the ruling class with this weapon and then cheer them on as they wield it against us.

Leave a comment