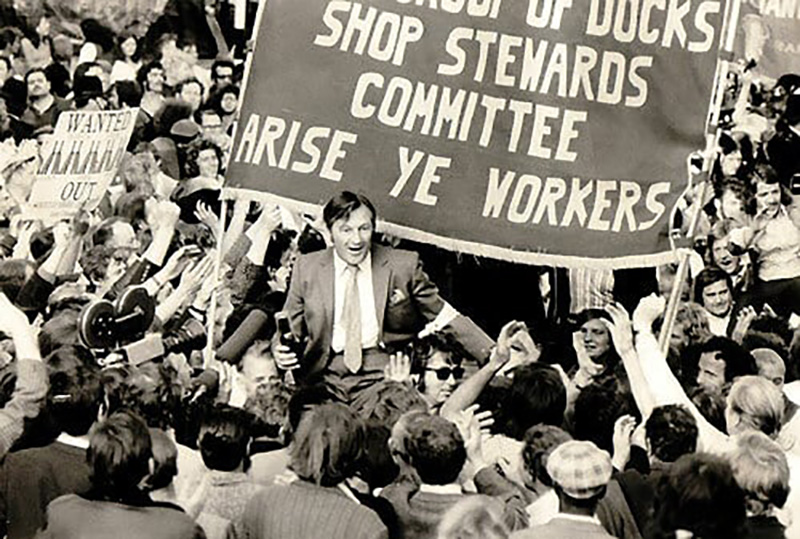

Infrequently, the Labour movement throws up a leader who is ahead of the rank and file politically. Someone who rejects the way forward, planned by the right-wing forces and introduces a programme that resonates with the masses.

Such a leader was the 21st Prime Minister of Australia, Gough Whitlam, whose leadership from December 1972 to November 1975 came to an abrupt halt when he was sacked by the forces of reaction involving the British Royal family and the CIA.

Whitlam was no revolutionary; he was simply a social democrat committed to building a progressive capitalist system. Once elected by the people he believed he could introduce policies that served their needs while maintaining the prevailing system of capitalism – a kind of capitalism with kindness, capitalism with less greed. Such a philosophy is not only an oxymoron, but also an absurdity, which Whitlam discovered to his detriment when his government was summarily terminated.

So just how progressive were his policies?

Despite serving for less than three years, Gough Whitlam’s government enacted a sweeping agenda of reforms that transformed Australian society. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 years. Universal healthcare was introduced. University tuition fees were abolished and needs-based welfare introduced by expanding social security, especially for single parents and the unemployed. In terms of racial equality, remnants of the White Australia Policy were ended and multiculturalism promoted. Free legal assistance became accessible to lower-income Australians.

In terms of indigenous rights, the first federal land rights legislation was introduced returning land to the Gurindji people at Wave Hill, symbolising a broader move toward indigenous land justice. There were cultural and educational reforms too. The Australia Council for the Arts, National Film and Television School were launched, and national heritage and creative projects were funded. There was massive school and urban infrastructure investment, and the independence of the ABC and public broadcasting were strengthened.

Economic and urban policies saw the creation of the Department of Urban and Regional Development to plan more equitable cities and regions. Policies for public housing, sewerage expansion, and improved public transport were introduced.

On top of all that conscription was ended, draft resisters were released from prison, and the first female judge was appointed to the Family Court. Phew! All achieved in under three years, illustrating that when the will exists and no impediments are put in the way by the ruling class, progressive programmes can be implemented.

Whitlam’s government recognised the People’s Republic of China (before the U.S. did), condemned apartheid in South Africa, took stronger independent stances in the UN and questioned and reduced Australia’s dependence on the U.S., particularly in relation to Vietnam and military bases like Pine Gap. This and the attempt to get national control over Australia’s natural resources with greater Australian ownership of minerals and energy, and pursuit of an independent foreign policy represented steps too far.

When you deviate from the capitalist roadmap

Whitlam’s government, while still operating within the bounds of parliamentary capitalism in a supposedly democratic nation, nevertheless represented a social-democratic challenge to entrenched capitalist and imperialist interests—both domestic and foreign.

Whitlam’s efforts to reclaim national sovereignty, expand public welfare, and assert democratic reforms were significant enough to provoke reactionary pushback from the ruling class, media elites, and U.S.-aligned institutions.

The sacking is a clear example of the limits of western democracy. While Whitlam was elected through parliamentary means, his reformist agenda clashed with entrenched capitalist and imperialist interests. Whitlam’s policies—like moves toward greater national control over natural resources, criticism of U.S. foreign policy (e.g., Vietnam War), and efforts to close U.S. spy bases (like Pine Gap)—threatened both domestic capitalists and U.S. imperialist interests. From this view, Whitlam’s dismissal was not just a domestic constitutional act but part of an international effort (led or backed by U.S. intelligence, e.g., the CIA) to ensure Australia remained a compliant junior partner in the imperialist system.

The state is not neutral—it exists to serve the interests of the ruling class. The sacking illustrated how unelected institutions like the monarchy-representing Governor-General can override elected governments when necessary to preserve bourgeois control. Whitlam’s downfall serves as just another lesson that true liberation and workers’ power cannot be achieved through parliamentary reform alone but requires revolutionary change.

Leave a comment