As the national anthem opened the start of the Premier League season at Wembley Stadium on Sunday for the Charity Shield, the red half of the stadium drowned it out with boos and whistles. It wasn’t the first time Liverpool fans have booed God Save the King (or Queen), and it won’t be the last, yet the media reacted with feigned shock at this act of defiance. Working-class fans had the audacity to boo the anthem of a monarch “long to reign over us.” This wasn’t a sudden fit of bad manners from football supporters, but the latest chapter in a city’s long history of defiance against a ruling class that has spat on Scouse workers.

I was at Wembley for Liverpool’s Charity Shield match against Crystal Palace, travelling down with my son and a busload of native Scousers. From my seat high in the Liverpool end of Wembley, I booed too — without shame. I’m of the city, I support the club, and I am working class. The idea that booing the national anthem is somehow disrespectful to England or other English fans is laughable. God Save the King is a throwback to a time when our rulers claimed to be anointed by God, their bloodline inherently superior, giving them the right to rule. The song is not for the people; it is anti-worker.

In football, it’s painted as a chest-pounding anthem of national unity, especially abroad. In reality, it’s a reminder of our position in society: that the ruling class own us, and we should thank them for it.

Simon Jordan, ex-chairman of Crystal Palace and petit-bourgeois entrepreneur, was on TalkSport after the game discussing the booing. He predicted Liverpool fans would bring up the managed decline of the 1980s and the lies of Hillsborough as to why we boo, then told us we should “keep our opinions to ourselves.” Sit down and shut up, plebs. Your opinion is only valid if you’ve reached a certain level of wealth and respect.

That attitude has always coloured the way Liverpool is discussed. The city has long been defined by sharp class contradictions. In the industrial boom of the 1800s, Liverpool became one of Britain’s most important ports, fuelled by the transatlantic slave trade and the shipping of raw materials. Wealth poured into the city, but only into the pockets of merchants and shipowners. Dockers and warehouse workers laboured in brutal, low-paid, casualised conditions. The famine in Ireland drove thousands here, shaping the city’s class makeup for generations.

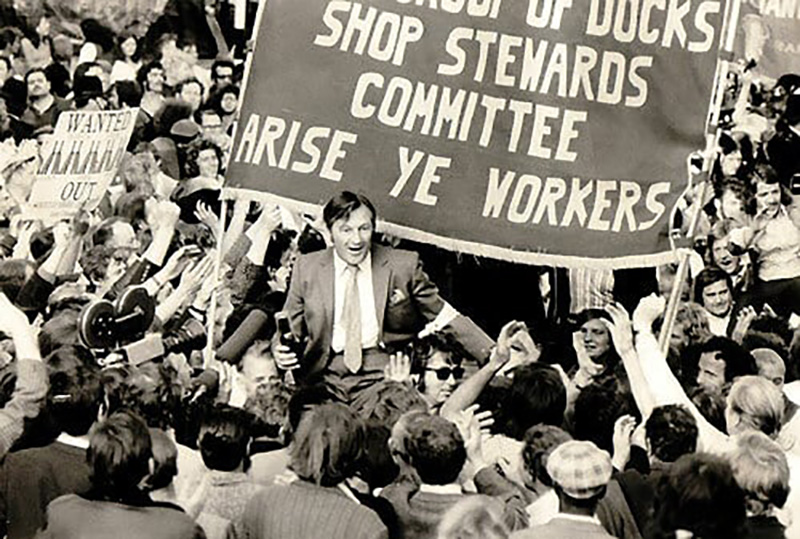

Liverpool’s battles with the establishment are as old as its industries. Regular dock strikes in the 1800s were met with repression and violence. The 1911 Transport Strike saw 70,000 workers down tools, and Westminster once again reached for the stick: Winston Churchill sent in the army and even a navy gunboat up the Mersey, its weapons aimed at the city.

The 20th century brought more struggles. From conscription resistance in WWI, the wildcat dock strikes of the ’50s and ’60s, the Toxteth uprising, and the Militant council’s refusal to bow to Thatcher, to the managed decline of the city, Hillsborough, and the 1994 dock lock-out. Injustice is a live wound here. The Sun, a best-selling paper across England, has faced a total boycott for decades over its vile lies about Hillsborough.

We could go deeper, into the city’s Irish republicanism, its strong communist movements of the 1920s, or the influence of Welsh, Danish, Chinese, and Russian communities. Liverpool hosts the oldest Chinatown in Europe, and its politics stretch back to the support of Parliamentarians under Cromwell against the monarchy. The siege mentality of Liverpool is much more than a few Trotskyists refusing to set a budget in the ’80s, as Simon Jordan would have you believe. Booing the anthem is not mindless. It is the sound of a city at odds with the British establishment. “Scouse, not English” is not Liverpool against the country, it is class consciousness passed down through generations. When we boo, we’re booing the monarchy, the state, the bankers, the media, and every enforcer of their power

Leave a comment