The owls are the latest venerable football club facing financial armageddon.

Choosing a football club is something of a rite of passage for working class people in England. I grew up in a small town half way between Manchester and Sheffield. It was the mid 1990s and Manchester United were just starting their long period of dominance of the domestic league. Everyone at my school thus ran towards the Red Devils in a wave of glory hunting. For reasons that I can only describe as contrarianism I chose to support Sheffield Wednesday, the owls, whose ground was a thirty mile drive away over the pennines. The first game I went to was Sheffield Wenesday vs Queens Park Rangers on February 17th 1996. QPR are my fathers team, him being a native of North London, and at first I was delighted when Graham Hyde, Wednesday midfielder, opened the scoring with an impressive volley from the edge of the penalty box that whipped past QPR keeper Jurgen Sommer. This joy was brief as QPR turned it around and the Owls lost 3-1 in the end. Needless to say my father enjoyed that game far more than I did. Little did I know though that the 1995 to 1996 season marked the point at which Sheffield Wednesday would start a dangerous gamble under the ownership of Dave Richards. They would start borrowing large amounts of money to try and keep pace with the bigger Premier league teams. This kicked off the accumulation of a gigantic amount of debt that the Owls have never managed to recover from. In this article we will be exploring why one of the oldest teams in the football league is now threatened with extinction due to the massive accumulation of debts.

Sheffield Wednesday Football Club, an institution whose name is woven into the very fabric of English football history, finds itself battling a profoundly modern and existential threat. The Owls, a club that evokes memories of packed terraces at the grand Hillsborough stadium, legendary players like Chris Waddle, David Hirst and Des Walker from the Ron Atkinson and Trevor Francis sides of the early 1990s, and a proud, enduring presence in the top flight, is now ensnared in a financial crisis that is both acute and chronic. To understand the full gravity of the present predicament—a club failing to pay its players, under transfer embargoes, and publicly feuding with its own fanbase—one must look beyond the current owner. The roots of this decay stretch back over two decades, to the club’s final years in the Premier League, where the seeds of financial mismanagement were first sown. This is a story of a long-term decline, a tale of how a failure to adapt to the modern football economy, compounded by a series of gambles and missteps, has brought a giant to its knees.

The Premier League Folly – The Debt Begins (1990s – 2000)

The common narrative points to the tumultuous reign of Thai steel magnate Dejphon Chansiri as the sole source of Wednesday’s woes. However, this is merely the latest, and most severe, chapter. The origins of the financial fragility trace back to the club’s last stint in the top division, a period that should have been one of consolidation and growth.

In the early 1990s, Sheffield Wednesday were a force. Under the management of Ron Atkinson and later Trevor Francis, they finished third in the Premier League, won the League Cup (1991), and reached the finals of both domestic cups in 1993. This on-field success, however, masked a dangerous financial strategy. Flush with the initial influx of Premier League television money and the ambition to compete with the emerging elite, the club embarked on a significant spending spree. High-profile signings like Paolo Di Canio, Benito Carbone, and Wim Jonk arrived on substantial wages.

The critical error was how this ambition was funded. Wednesday’s spending was largely financed through debt. The club took out huge loans against future earnings, betting that perpetual Premier League status and continued European football would service the debt. This was a catastrophic miscalculation. After finishing seventh in 1997, Wednesday’s form dipped dramatically. Key players aged, investments in young talent did not pay off, and by the 1998-99 season, the unthinkable happened: relegation to the second tier.

The fall was devastating. The club was suddenly saddled with a Premier League wage bill—including the astronomical salaries of players like Carbone—while generating Football League level revenue. The debt, which had been manageable in the top flight, became a dead weight. This period established a dangerous precedent: the club was willing to mortgage its future for short-term gains, a philosophy that would haunt it for the next twenty years.

The Wilderness Years – A Slow Decline (2000 – 2015)

The two decades following relegation were a story of stagnation, administration, and missed opportunities. The debt from the Premier League era never truly disappeared; it was restructured, refinanced, and lingered like a shadow.

In 2002, the club’s hand was forced. The weight of its financial obligations, coupled with declining gates and a lack of investment, became too much to bear. Sheffield Wednesday entered administration in 2010 with debts of over £30 million. This was a direct consequence of the financial model established in the 1990s. The points deduction that followed confirmed a grim new reality: Wednesday were no longer a fallen giant hoping for a quick return; they were a crisis club fighting for its life in the second and third tiers.

A brief respite arrived in the form of local businessman Dave Allen, and later, the takeover by Milan Mandaric in 2010. Mandaric, former owner of Portsmouth, stabilised the club somewhat. He navigated it out of administration, implemented a more sustainable wage structure, and oversaw a gradual recovery. However, the Mandaric era was one of austerity. The focus was on survival, not ambition. Hillsborough fell into a state of disrepair, the squad was assembled on a shoestring budget, and the club treaded water in the Championship. While this prudence was necessary to correct past excesses, it created a fanbase hungry for ambition and a return to former glories. This hunger would make them uniquely susceptible to the promises of a saviour, setting the stage for the next, and most damaging, phase of the crisis.

The Chansiri Gamble – Boom and Bust (2015 – Present)

The 2015 takeover by Thai steel magnate Dejphon Chansiri was met with unbridled optimism. Here was a wealthy owner promising to restore Wednesday to the Premier League. Initially, he delivered. He invested heavily, breaking the club’s transfer record multiple times to sign players like Fernando Forestieri, Gary Hooper, and Adam Reach. Under the management of Carlos Carvalhal, the team played attractive, attacking football and reached the Championship play-offs in 2016 and 2017, narrowly missing out on promotion.

Beneath the surface, however, the ghosts of the 1990s were reawakening. Chansiri’s strategy was not one of sustainable building but of high-stakes gambling. The massive investment in the squad was not funded by club revenue but by Chansiri himself through interest-free loans. While this avoided external debt, it made the club entirely dependent on the owner’s continued generosity. The wage bill ballooned to become one of the highest in the Championship, far exceeding the club’s natural income from tickets, commercials, and TV rights.

This strategy collided head-on with the English Football League’s (EFL) Profitability and Sustainability (P&S) rules. The reckoning arrived in 2020. To circumvent the P&S limits, the club engaged in a controversial sale of Hillsborough stadium to a company owned by Chansiri himself for £60 million—a price many independent valuers considered significantly above market rate. The EFL investigated and determined the sale was an attempt to artificially inflate the club’s profit for the accounting period. After a long and acrimonious legal battle, the outcome was severe: a 12-point deduction for the 2020-21 season (later reduced to 6 on appeal). The punishment achieved what poor form had not: it relegated Wednesday to League One.

The Perfect Storm – Relegation and Collapse

Relegation to the third tier severed the club’s most vital financial artery: Championship broadcast revenue. The legacy of Chansiri’s gamble was a squad packed with players on multi-year, high-value Championship contracts, now playing in a league with a fraction of the income.

The club is now trapped in a vicious cycle:

1. **Crippling Wage Bill:** A significant portion of its diminished revenue is consumed by a wage bill utterly disproportionate to League One.

2. **Owner Withdrawal:** Chansiri, having claimed to have lost over £200 million, has publicly stated he will no longer cover the monthly shortfalls. This has led to the repeated failure to pay players and staff on time.

3. **EFL Sanctions:** These late payments and historical breaches have led to transfer embargoes, preventing the manager from strengthening the squad, thus hampering on-pitch performance and the chance of promotion.

4. **Eroding Assets:** The club’s infrastructure, notably Hillsborough, is showing signs of neglect. The stadium has been used as collateral, risking the club’s crown jewel.

The relationship between the owner and the fanbase has broken down entirely. Chansiri’s public statements, blaming supporters for a lack of financial support and accusing them of undermining the club, have created a toxic atmosphere. Protests are now a regular feature at matches, a sad spectacle for a support that continues to turn up in numbers that dwarf their third-tier rivals.

A Club at a Crossroads

The financial crisis at Sheffield Wednesday is not a single event but a disease with a long incubation period. It began with the leveraged ambition of the 1990s Premier League era, was exacerbated by administration in the 2000s, and has been catastrophically accelerated by the boom-and-bust model of the Chansiri years. It is a perfect case study in how not to run a football club.

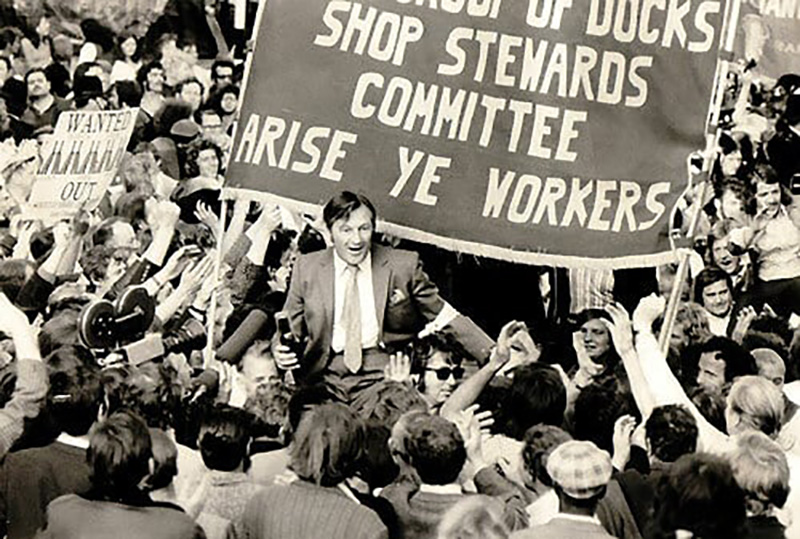

The unfortunate reality though is that the Owls are only one example of how the Premier league has ushered in an era of unsustainable spending financed by the accumulation of debts. As the miserable story of Sheffield Wednesday shows the legacy of debts incurred a generation ago continues to cripple clubs to this day. The only solution for clubs like Wednesday is to move to being a purely fan owned operation. It can no longer be the case that we as fans must await a “saviour” as no such savior exists. As the Chansiri era shows, no capitalist is prepared to take on the risks associated with managing a debt riddled club. Fans must be prepared to ditch the idea of returning to the Premier league. This is a trap that only brings debt and disaster.

Leave a comment