The Homelessness Crisis In Glasgow Is Caused By A Parasitic, Decaying Capitalism

For decades, Glasgow’s identity was intertwined with its council estates and high-rise towers, not as symbols of destitution but as pillars of community and security. They were the legacy of a post-war determination to clear the infamous slums and provide “homes fit for heroes.” Today, that legacy is in tatters. The city now faces a situation where the demand for safe, secure, and affordable social housing drastically, and tragically, outstrips supply, creating a chasm into which thousands of individuals and families are falling.

Anyone walking around the streets of Glasgow these days will be brought face to face with an ever growing number of homeless people. According to a recent story in The Herald newspaper the situation is rapidly worsening with 700 people being turned away from emergency accommodation by Glasgow city council in between April and July of this year. How did this happen? How did Glasgow come to be a city with this ever growing problem? The answer lies in the decades long destruction of public housing, a trend started by the Tories but not stopped by the devolved governments in Scotland led by the SNP and Labour.

A Historical Promise Broken

To understand the present crisis, one must look to the past. The Glasgow of the 19th and early 20th centuries was a city defined by overcrowding. The tenement slums, though often romanticised, were frequently squalid and inhumanely cramped. The response was one of the most ambitious public housing programmes in Europe. From the mammoth Red Road flats to the sprawling estates of Easterhouse, Castlemilk, and Drumchapel, the city council embarked on a mission to rehouse its population. While these developments later faced criticism for poor planning and social isolation, their intention was unequivocal: to provide housing as a public good.

The turning point, widely identified by housing charities, academics, and activists, was the Britain-wide introduction of the ‘Right to Buy’ policy in 1980. This policy, which gave council tenants the right to purchase their homes at a significant discount, was designed to transform housing from something that was seen as a public good into a source of profit. In Glasgow, its long-term impact was devastating. It was a one-way valve: over 130,000 council houses were sold off in Scotland, and crucially, the legislation prevented councils from using the receipts from these sales to build new homes to replace them. The city’s social housing stock was being asset-stripped, its numbers dwindling year on year without replenishment.

The policy did not just reduce numbers; it cherry-picked the best properties. The most desirable houses with gardens were the first to be bought, leaving councils as landlords of last resort, increasingly managing only the hardest-to-let homes in the most deprived areas. This accelerated the stigmatisation of social housing and concentrated poverty, undermining the very communities it was supposed to help.

The Perfect Storm: Stagnant Supply and Soaring Demand

The consequences of this decades-long drain have collided with modern economic pressures to create a perfect storm. Today, Glasgow City Council is one of the largest landlords in Europe, but its stock stands at around 70,000 properties, a fraction of what it once was. Meanwhile, the waiting list for a council house in the city contains tens of thousands of names. In 2023, over 25,000 applications were vying for social housing, with thousands of households classified as high priority due to homelessness.

This supply-demand imbalance is catastrophic. For those on the brink—fleeing domestic abuse, facing eviction from a private let, or dealing with a relationship breakdown—the safety net of social housing is now impossibly thin. There is simply nowhere for them to go. This logjam has a domino effect throughout the entire housing system. People who would once have moved into a secure council property remain stuck in the expensive and unstable private rented sector (PRS), which in turn reduces available properties and drives up rents for everyone else.

The PRS is a notoriously insecure tenure for those on low incomes. The freeze on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic provided temporary relief, but its end unleashed a wave of Section 21 “no-fault” evictions. Soaring rents, driven by demand and the broader cost-of-living crisis, mean that even a full-time minimum wage job is often insufficient to cover the cost of a modest flat in Glasgow. A single unexpected bill, a period of ill health, or a reduction in working hours can be all it takes to tip a household from precarious stability into arrears and, ultimately, homelessness.

The Human Cost: Beyond the Statistics

The crisis is measured in more than numbers; it is measured in human suffering. The lack of public housing means that when someone presents as homeless to the council, the statutory duty to house them often cannot be met with a permanent home. Instead, they are funneled into a labyrinth of temporary accommodation.

This includes B&Bs, hostels, and budget hotels, often described as “unsuitable” by charities like Shelter Scotland and Crisis. These are places where families are forced to live in a single room for months, if not years, with no space for children to play or do homework, and often with shared facilities with other vulnerable and sometimes traumatised individuals. The psychological toll is immense, exacerbating existing mental health issues and creating new ones. It is a system that manages the crisis but does nothing to solve it, trapping people in a state of limbo and hopelessness.

The visible rough sleeping population—the most acute and vulnerable manifestation of homelessness—is also directly linked to this shortage. For those with complex needs, such as addiction or severe mental illness, the pathway to stability is almost impossible without a stable home. The “Housing First” model, which provides unconditional, permanent housing alongside wrap-around support, has proven hugely successful. However, its rollout in Glasgow is hamstrung by the same fundamental problem: a crippling lack of available homes to use for the programme.

The Need for Radical Action

Acknowledgment of the problem is growing. The Scottish Government has declared homelessness a “public health emergency” and has introduced progressive legislation, such as the Homelessness Prevention Duties and the upholding of the Unsuitable Accommodation Order, which aims to limit time spent in B&Bs. Glasgow City Council and Housing Associations are building again. New social homes are being constructed, and ambitious targets have been set.

Yet, the pace and scale of building are not matching the scale of the deficit. Construction is hampered by planning delays, rising costs of materials, and budgetary constraints. Building a few hundred new homes a year is a positive step, but it is like using a thimble to bail out a sinking ship when the need is for thousands.

Radical action is required to solve the homelessness crisis facing all of Scotland. To that end we think that the demands put forward by the Scottish tenants organisation should form the basis for campaigning on the housing crisis.

- To immediately engage in a massive public investment programme of building tens of thousands of public sector homes, especially council homes, to house all of the homeless population and the near 250,000 people on the social housing waiting list.

- Funding a large-scale renovation of thousands of empty houses and turning them into good quality homes for working-class families.

- A large increase in direct investment in construction industry apprenticeship schemes to enable and sustain the building of more public sector homes in the future.

- All local authorities to be given proper funding to directly build and own suitable temporary accommodation for homeless people with the emphasis on providing good quality women-only temporary accommodation so that women are protected from male violence and their complex needs are addressed.

- That all public funding by local authorities of private operators of homeless hotels should cease and instead saved resources be given to implementing the creation of proper single-sex accomodation for homeless women and children.

- To implement direct investment to improve existing social housing stock in Scotland to eradicate damp and mould to fundamentally improve the indoor enirvonment of these homes so they are healthy places to live.

- Ensure fair and affordable rent for all tenants in Scotland enabling a real reduction in rents for all Scottish tenants in the private and social rented sectors.

- An end to all evictions in the private and social rented sectors for rent arrears with all rent debt being written off.

- To break monolithic, semi- privatised housing associations such as the Wheatley Group, which are totally undemocratic and unresponsive to tenant needs. Instead proper tenant-led control of social housing should be established.

- Give tenants the right to transfer back to council housing in Scotland and out of the control of housing associations.

- Ensure that there are restrictions on private finance in social rented housing especially not allowing the for profit model of finance in Scotland to stop any long term increase in rents.

- To reduce dependance on the private rented sector in Scotland by greatly increasing funding for public sector housing so that local authorities can more easily use their considerable power through compulsory purchase orders to buy up properties in the private rented sector.

- Ensure no public subsidy is available for home ownership in Scotland as precious resources are needed to house thousnads of low income families.

- An end to mid-market rented developments as all resources have to be devoted to housing the homeless and those on social housing waiting lists in public sector homes.

- Proactive planning policies that ensure that public sector housing is available in good central locations in towns and cities and that there are restrictions imposed on private build to rent and private student developments in town and city centre locations.

- Encourage and support the emergence of genuine independent tenant and resident organisations.

- To give tenants the right to control their local housing stock so they can make meaningful decisions to improve their communities.

- An end to demolitions of public sector homes in all communities where there is no demand for it.

- Make sure there are no barriers to access public sector housing in line with all anti-discrimination laws.

Were these demands to be adopted it would pose a fundamental challenge to the for profit housing model. This is why such demands must be taken up and campaigned for seriously by the entire working class movement. The housing crisis can only be solved by ending profiteering and not allowing governments to continually inflate the house price bubble at the expense of the working class.

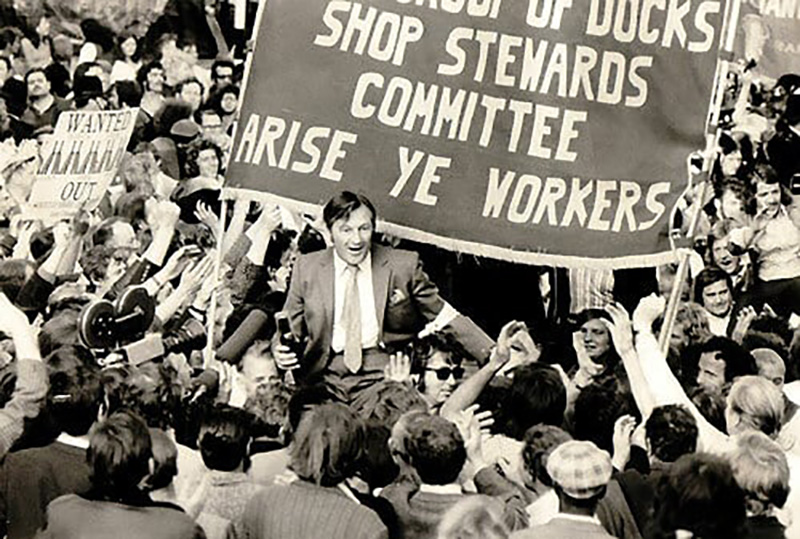

The sight of homelessness on Glasgow’s streets is not an inevitability; it is a policy choice. It is the result of a decades-long choice to disinvest in the idea that a safe, secure home is a basic right. Re-weaving the social fabric torn by this neglect will be the work of a generation. It begins with a fundamental recommitment to the principle that provided the foundation for the city’s transformation once before: that housing for all is not a cost, but the bedrock of a healthy, just, and functioning society. These are demands that every trade union should make and popularise amongst their membership, these should be demands that the entire working class movement is mobilised to fight for. The profits made by the property developers and banks from the housing crisis are immense and they aren’t going to give those up willingly. It will take a sustained fight against these interests if we are to even gain a modicum of success against the growing housing crisis. Ultimately, we must move away from the capitalist system which sees even the most essential elements of human existence, such as housing, as a source of profit and move to a socialist system where the essentials of life are provided and we can be liberated from constant striving just to be able to survive.

Leave a comment