French Farmers once again as they drove their parade of over 350 tractors towards Paris, we thought it was about time we took a look at what has caused this uproar.

For most of the post-war period, French agriculture was able to avoid being treated as a free-market sector. Farmers were recognised as a social class whose stability was paramount. Food security, rural employment, and the survival of the countryside were political priorities, not for the market to profit from.

That settlement was built into the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) when it was established in the 1960s. Guaranteed prices, quotas, and state intervention were not luxuries; they were the price paid to prevent rural collapse and food dependency. Farmers were rarely prosperous, but farming was vital to the country’s stability and was a viable way of making a half decent living. That model has been dismantled step by step for over thirty years.

From protection to exposure

The decisive break came in the early 1990s. The MacSharry reforms of 1992, followed by the Fischler reforms of 2003, shifted CAP away from price protection and toward market exposure. Subsidies were ‘decoupled’ from production. Quotas were phased out. Farmers were told to join market competition. This was spoken as modernisation, but the reality was exposure to the desires of capital.

French farmers were pushed into global markets while remaining bound and being hamstrung by national and EU regulation. They were no longer protected from price volatility, but they were still responsible for meeting environmental, safety, and welfare standards. The risk was now theirs without government protection. At the same time, agriculture itself was being reorganised.

Who gained as the farmers lost?

Over the same period, the agri-food chain concentrated rapidly. A small number of supermarket groups, Carrefour, Leclerc, Intermarché, Auchan, came to dominate food retail. Large processors and exporters set contract terms. Input suppliers were monopolised, driving up the cost of fertiliser, seed, fuel, and machinery. As capitalist ‘competition’ always will.

Farmers were pulled apart at both ends. They paid more to produce food and received less for its sale. Many survived only through borrowing. In large parts of France today, average farm income falls below the minimum wage, and debt is unavoidable rather than exceptional. An awful result of this is farmer suicide rates. They have long been acknowledged as unprecedentedly high, which is just another symptom of this profit-driven pressure, not a personal tragedy disconnected from economics. This isn’t about lazy farmers or outdated methods. That line is a lie, and everyone involved knows it.

Why the protests have erupted now

The current wave of protests didn’t appear suddenly. It was triggered by pressure finally converging from three directions. First, EU trade agreements, particularly the proposed EU–Mercosur deal, threaten to open European markets to large volumes of agricultural imports produced under lower labour and environmental standards. Farmers are expected to compete on price while obeying rules their competitors do not. Second, regulatory tightening has continued without protection. Environmental measures, pesticide restrictions, and reporting requirements are imposed without price guarantees or adequate compensation. Farmers are not rejecting environmental responsibility, they are rejecting how it is being weaponised and they are being ruined by it. Third, price suppression by retailers has intensified. Even during inflation, farm-gate prices have failed to rise in line with costs. Supermarkets protect margins; farmers suffer the loss. At this point, the shape of the problem is already clear.

How the protests have developed

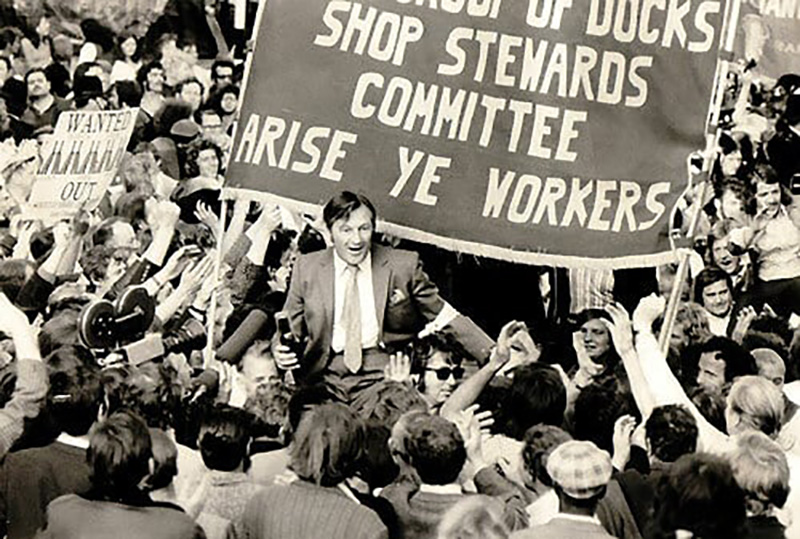

The protests spread quickly and nationally. Tractor blockades, motorway closures, and city-centre demonstrations were not symbolic or limited by trade unions as British workers’ strikes can be, they were expressions of a class that had run out of room to manoeuvre. Protest was a must before they lost out completely.

Government responses have been predictable of any capitalist government: fuel rebates, temporary delays, limited (if any) concessions. What has been avoided (and is probably impossible at this point of decaying capitalism) is any reversal of the underlying policy direction. No restoration of price protection. No challenge to global supermarket power. The French government is happy to leave an important trade exposed.

The protests continue because nothing fundamental has changed. This is treated as modern inevitability, not profit driven decisions or capital. This crisis was not caused by weather, inefficiency, or stubbornness. It is another symptom of capitalism.

- EU policymakers dismantled protection to allow big business to monopolise.

- French governments enforced liberalisation while blaming Brussels.

- Supermarket chains used buying power to suppress prices.

- Agri-industrial exporters benefited from scale and trade access.

- Banks and finance profited from permanent indebtedness.

- Farmers are disciplined from above and undercut from below while value is extracted elsewhere.

The EU’s role

The EU did not stumble into this situation. It reorganised agriculture deliberately. Under the current model, farming is treated as a competitive sector rather than a social necessity. Small producers are expected to ‘adjust’, merge, or disappear. Trade policy is designed for exporters. Environmental responsibility is individualised instead of collectively supported.

This approach contrasts sharply with how agriculture was organised under socialist planning in the Soviet Union. Collective farming there was not built around competition between producers or exposure to global markets, but around planned production. Farms were integrated into a wider economic plan that ensured stable prices, access to machinery, fuel, fertiliser, and guaranteed outlets for produce.

Crucially, collectivisation was not about creating private monopolies. It was a response to the destructive effects of market anarchy in agriculture, chronic shortages, peasant indebtedness, and price collapse. While the system had contradictions and was shaped by material conditions, it did not subordinate food production to supermarket monopoly margins or financial speculation.

Where capitalist agriculture concentrates power with capitalist monopolies, collective farming subordinated production to social need rather than capital. Farmers were not treated as isolated market actors competing against one another, but as part of a planned system based around need rather than enrichment of one class over another.

The EU’s agricultural model does the opposite. It dismantles collective protection, exposes producers to global competition, and allows monopoly buyers to dictate terms, while still enforcing regulation that only harms workers production. What is presented as ‘modernisation’ is, in reality, the replacement of collective security with market discipline.

Conclusion

French farmers are striking because capitalism has made farming unworkable.

Market competition is being imposed on a sector that cannot function as a competitive market without destroying producers. Food production is treated like any other commodity, exposed to global price fluctuations, trade deals, and monopoly capitalism, while the people who actually produce it are left to absorb the risk.

The European Union accelerates this process. As a capitalist trading bloc, it organises agriculture around market competition and corporate supply chains. Protection is dismantled, markets are opened, and farmers are told to struggle on or die. Regulation remains, but collective security does not. The result is predictable: concentration of market forces and collapse of worker run farms. This is not a failure of implementation. It is the outcome of a system built on competition rather than population need. Agriculture cannot be left to the market without producing shortages, instability, and ruin for smaller producers. Farming only functions for the people when it is planned, when prices are stable, production is coordinated, inputs are guaranteed, and food is produced to meet social need rather than profit margins.

The French farmers’ revolt is not just a protest against trade deals or regulation. It is an indictment of capitalism’s inability to organise food production rationally. As long as agriculture is subordinated to markets and competition, these crises will repeat. If farming is to serve the population, and if farmers are to survive, then a planned economy is paramount

Leave a comment