A pivotal period in the modern history of the British trade union movement is undoubtedly between the years of 1984 and 1986.

The Government of Margaret Thatcher, having learnt the lessons of the industrial and electoral defeats of the Ted Heath Government of 1970-1974 at the hands of the working class, planned and waged an aggressive war against workers in two key disputes in the 1980s: The Great Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 and, arguably as significantly, the Wapping print dispute of 1986.

Among the many common threads linking these two huge defeats for the working class is a long-defunct trade union which became a pariah in the labour movement and will serve in perpetuity as an object lesson in the potential for reaction, racism and class treachery that exists within the self-proclaimed progressive movement that is British Labourism. That trade union was the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union, known to its members and those that came to know and loathe it as the EETPU.

The EETPU was formed in 1968 through a merger of two trade unions: The Electrical Trades Union (ETU) and the Plumbing Trades Union (PTU). As is often the case in mergers of trade unions, the newly-formed union is dominated by the most active and, in some cases, most militant participant in that merger. In the case of the EETPU, the most active participant was the ETU, and it is that political activity, particularly in the period from 1956 until its merger in 1968, which set in train the development of the union into the collaborationist, Government-informing and treacherous organisation that it became.

British Communists faced a crisis of faith of sorts in the 1950s. The publication of the CPGB’s disastrous “Britain’s Road to Socialism” document in 1951 clearly laid out the party’s rejection of revolutionary Communism and instead adopted reformism through purely parliamentary means via the vehicle of the imperialist Labour Party.

Further to this, the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the subsequent ascension of Nikita Khrushchev to General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union led to a period of ‘de-Stalinisation’: Repeated, public and pronounced repudiation of Stalin and the ‘cult of personality’ that Khruschchev claimed surrounded him, as well as the dismantling of the economic and cultural legacy Stalin left with his passing.

These events, as well as the Communist’s response to uprisings in Poland and Hungary in 1956, led some notable CPGB-member trade unionists to either quit the party or to go even further and become avowed anti-Communists.

One notable exemplar of this seismic shift from Communist to anti-Communist politics was Frank Chapple. Chapple (who was to subsequently become Baron Chapple of Hoxton) joined the CPGB in 1939 was an active Communist organiser, including during his service during World War II in the Royal Ordnance Factories and the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers in both France and Germany. He became a member of the ETU’s Executive Committee in 1958 and left the CPGB to join the Labour Party in 1959, when he became a ferocious anti-Communist.

As was the case in many trade unions of the time, the influence of members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) grew exponentially in the post-war period. In the case of the ETU, this was signified most starkly by the elections of CPGB members Frank Foulkes as ETU President in 1946, and Walter Stevens as the union’s General Secretary in 1948.

Chapple threw his support behind an anti-Communist candidate for ETU General Secretary, Jock Byrne, when an election for the General Secretary position took place in 1959. Byrne was widely considered to be the favourite to win the election, but narrowly lost to the incumbent, Frank Haxell.

Les Cannon, a former ETU Executive Committee member and CPGB member turned anti-Communist, was forced to stand down from his Executive position in 1954 when he successfully secured a position at the ETU’s member training school in Esher. This was because, by taking this tutoring role, he became an employee of the union and so was ineligible to remain on the Executive, a situation Cannon apparently neither anticipated or accepted.

Following the election defeat of Jock Byrne for the General Secretary position in 1959, Cannon began his own investigation into what he believed had been vote rigging within the union. He alleged that he had uncovered over 100 instances of branches being barred from voting in the 1959 General Secretary election and other elections, in many cases owing to ballot papers arriving late, according to accounts by the union. Cannon asserted that these branches had returned their paperwork in good time and further alleged that CPGB members within the union had rigged these elections in order to favour Communist Party members.

In 1961, Jock Byrne and Frank Chapple, supported by Les Cannon, took General Secretary Frank Haxell, President Frank Foulkes and thirteen other CPGB members of the union to court, alleging vote-rigging at the highest levels of the union. The court ruled that the 1959 ETU General Secretary election had been rigged and installed Jock Byrne as the GS in a decision that could be argued as inevitable as soon as anti-Communists had taken to the services of the British judiciary in accusing Communists of malfeasance.

Frank Foulkes argued that he was unaware of any voter fraud, but lost a subsequent court case in 1962 on the grounds that he at least should have been aware of vote-rigging by dint of his seniority within the union and the at least implied assertion in court that, given that he had been the union’s President since 1945, nothing could happen within the ETU without Foulke’s knowledge. Foulkes took early retirement following his court defeat. With Jock Byrne in place at General Secretary, followed by Les Cannon’s election as ETU President in 1962, the balance of power at the top to the union had shifted from a pro-Communist to a vehemently anti-Communist position and a purge of Communist Party members within the union began.

The TUC General Council ruled that the ETU must bar its existing Executive office-holders for five years following the High Court cases alleging CPGB vote-rigging. When the ETU refused, they were expelled from the TUC. This was a false dawn for the Communists at the senior level of the union, as they were driven out under new High Court-mandated procedures put in place with the full support of the mass media. Cannon and Byrne, with Chapple elected as Assistant General Secretary, oversaw a seismic shift in the political balance of the Executive Committee to a predominately rightist position, with nine out of eleven posts on the Executive taken by members considered to be of the right.

With this ‘rightist’ platform, along with vehement anti-Communists in position as General Secretary and President, the union began a long and, from their perspective, successful process of purging Communists from the union once and for all. This also set in train the shift in the union’s approach to organising their own membership and tackling attacks from employers and the Government to wholly collaborationist and class-consensus methods, which would be exemplified by the abominable individual Eric Hammond.

Hammond ascended to the position of General Secretary of the EETPU in 1984, sixteen years after the new union came into existence and following the ending of Frank Chapple’s eighteen year tenure. Chapple had marked his term of office by criticising then Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s attempts to curb wage demands and create class consensus (including in the now infamous White Paper ‘In Place of Strife’) and yet opposing the Trades Union Congress’s shift to the left as the working class faced head-on the labour ‘reforms’ rammed through by the Conservative Ted Heath Government.

Chapple claimed that these reforms had to be proven to be unworkable on their lack of merit rather than opposed on their face, a position which put him at odds with the majority of the TUC General Council, of which he was a member. Chapple’s relationship with the Labour Party became increasingly fraught, culminating in his pledging open support in 1981 for the renegade Social Democratic Party, whose creation was a huge factor in the heavy defeat which Labour suffered at the 1983 General Election. Despite his deep unpopularity amongst his peers on the TUC General Council, some of whom were unreserved in their charge that he was a traitor to the working class, Chapple became the President of the TUC in 1982.

Afforded yet another opportunity to confirm his status as one of the labour movement’s most despised trade unionists, Chapple made an excoriating speech at 1983 TUC Congress, where he attacked his trade union colleagues: He accused them of being weak, undemocratic and, possibly most abominable of all as far as Chapple was concerned, left wing. He retired as General Secretary of the EETPU and President of TUC in 1984 and was rewarded for his class treachery the following year by being made a life peer.

Hammond was in many ways a continuity candidate to Chapple – a staunch anti-Communist and strong supporter of the imperialist Labour Party, he was unabashed in his open hatred of what he called the “lunatic left” and refused to allow any political organisation to make use of the union’s offices. In fact, Hammond’s rabidly right wing politics and enthusiasm for conspiring with employers and the State against striking workers made Chapple look like a moderate in comparison.

In 1983, Hammond attempted to join the Confederation of British Industry, arguing that, as the EETPU was an employer who provided training, he was entitled to join the throng of arch-exploiters that the CBI was and is to this day. He was turned down, but was invited to speak at a later CBI conference and Hammond even invited the despised Thatcherite henchman and staunch anti-trade unionist Norman Tebbitt to open the union’s new training centre in Kent. This was to be a portent for what was to follow in his eight years as General Secretary.

Also in 1983, in a speech that Hammond gave at TUC Congress, he attacked what he called “terrorists, lesbians and other queer people in the GLC [Greater London Council] Labour Party”. A running theme during Hammond’s tenure, particularly when engaging with other sections of the very movement of which he claimed to be part, was a flagrant disregard for criticism, or the disgust, that his stances and speeches created. In fact, he seemed to goad people with the most reactionary and inflammatory language in order to draw their ire.

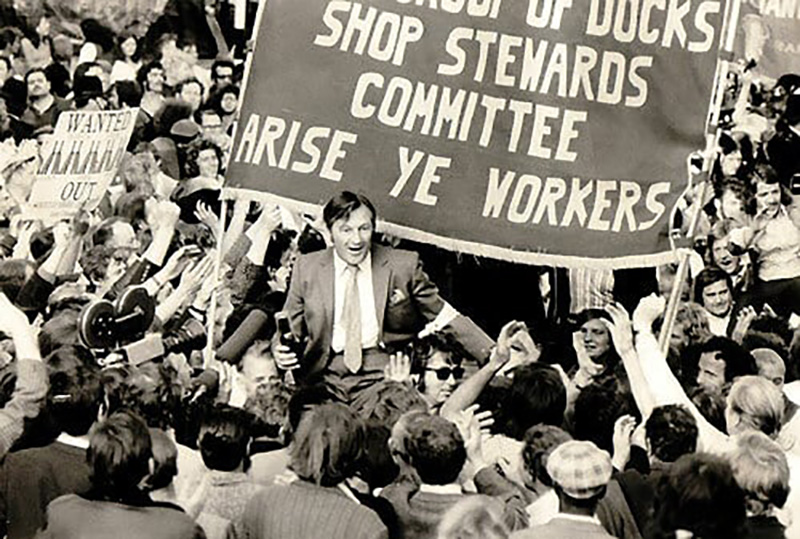

Hammond would frame his open collusion with employers and the State as a single-minded and determined strategy to defend the interests of EETPU members above any and all other considerations. However, he clearly revelled in the hatred and opprobrium his actions would draw from all corners of the labour movement. His union voted to oppose the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike – Hammond loathed Arthur Scargill and took the opportunity at Labour Party Conference in 1985 to take to the podium and state brazenly that the striking miners were ‘lions led by donkeys’ to boos and cat-calls from delegates. Ron Todd of the Transport and General Workers Union responded by saying that he’d “rather be led by a donkey than a jackal”, a clear swipe at Hammond.

But Hammond’s place in that small and select group of the labour movement’s most reviled members was assured with his actions during the ‘Wapping Dispute’ of 1986, when print magnate Rupert Murdoch relocated publishing of his stable of titles from Fleet Street to a new facility in Wapping, east London, and with it swept away some forty years of hot metal typesetting as a printing method, replacing it with computerised journalist-based digital typesetting.

Print workers at the time were amongst the highest skilled and well-paid members of the working class and their unions’ approach to protecting their status in this regard, often at the expense of other workers, made them vulnerable when new technology threatened to render obsolete the skills that their members possessed. While they would been cognisant of the potential threat posed by innovations in printing, the print unions could not have anticipated was that their greatest threat was posed by another trade union.

After a secret ballot in 1986, print workers voted to strike against Murdoch’s plans. Hammond had conspired with Murdoch to establish what became known as “Fortress Wapping”: An imposing building surrounded with security fences and barbed wire, in stark contrast to the buildings which adorned the then home of the British press in Fleet Street, three miles to the west of Wapping. In fact, the whole audacious project would not have been possible were it not for Hammond and his union agreeing to staff the new print works: The union actually assisted in the recruitment of these workers for Murdoch.

Despite the printers’ grievances and the fact that they had held a democratic ballot in support of strike action, Hammond was unrepentant that his actions and the actions of his trade union had created an existential crisis for 6,800 print workers employed at the old Fleet Street print works, to be replaced by a tenth of that number of EETPU members at Wapping. As far as he was concerned, he had acted in the best interest of his trade union and had created some 600 new jobs for the EETPU to recruit as members. In a bizarre twist, the Trades Union Congress selected Hammond to broker a peace deal with Murdoch.

The talks took place in Los Angeles, where Hammond stayed at the resplendent Beverly Hills Hotel, along with his national officer Tom Rice, at Rupert Murdoch’s expense. When discovered by a Daily Mirror reporter, the left were incandescent with rage and the dispute resulted in defeat for the former Fleet Street print workers and, in turn, signified the beginning of the end for the print unions themselves as other newspapers followed Murdoch’s lead and relocated to new locations away from Fleet Street and abolished hot metal and phototypesetting for good.

In 1988, the TUC expelled the EETPU over their ‘no strike deal’ policy, which involved approaching employers where union membership was low and opportunistically seeking what is known as a ‘sole recognition agreement’: Essentially making the EETPU the only union with which the employer would negotiate, compelling workers to join that union and that union alone, in return for a quid pro quo – a guarantee that the union would not organise strike action, regardless of their members’ grievances.

Hammond knew that expulsion was coming: He didn’t even book a hotel for himself for the entire duration of TUC Congress. When his union’s expulsion was confirmed in Bournemouth that year, Hammond stormed from the hall, throwing his identification card in the air as he left: An act of hubris which neatly encapsulated both him as a man and his term of office as General Secretary of Britain’s most loathed trade union. 5,000 members subsequently split from the EETPU and formed the Electrical and Plumbing Industries Union, while it was later discovered that the EETPU colluded with the Thatcher Government, advising Government ministers on how best to tackle left wing trade unions.

EETPU merged in 1992 with the Amalgamated Engineering Union to become the Amalgamated Engineering and Electrical Union. Via other mergers, it is now part of Unite the Union.

It is difficult to find a British trade union which had been so active and determined in its betrayal of the working class, particularly during the 1980s, as the EETPU. The Government of Margaret Thatcher had planned to wage war on the working class by peeling sections of industrially powerful workers away from the main body of the working class before destroying them group by group. None of this would have been possible were it not for the weakness of the TUC, the unequivocal implicit support of the Labour Party or the opportunism and treachery of the EETPU.

We should not lament its passing, nor the passing of Eric Hammond, who died in 2009.

Leave a comment