“You should have voted for Corbyn” is a common refrain, especially online, these days. Many people when looking at the terrible “choices” likely to be on offer at the next general election rightly ask themselves the question “what if Corbyn won?” This question is particularly asked in relation to the election in 2017 where the Labour Party came within a few thousand votes of a narrow electoral victory. It is worth asking the “what if” question with regard to a potential Corbyn led government.

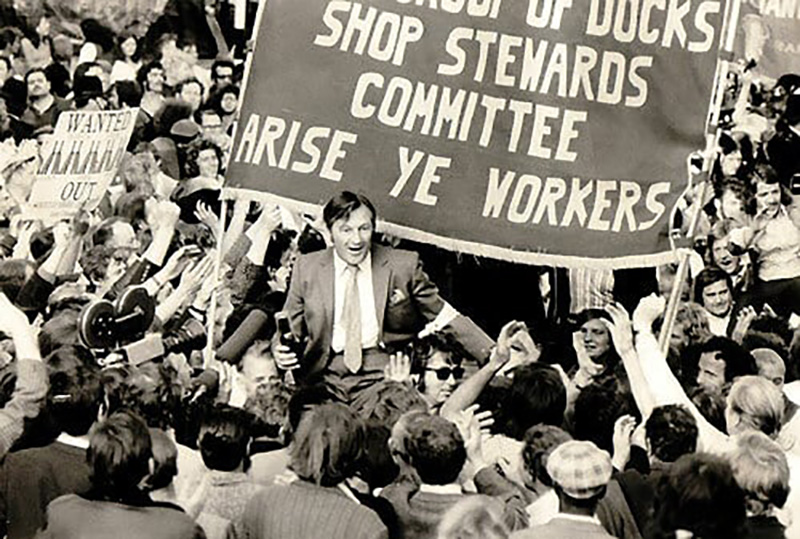

The first thing that must be noted is the extreme level of opposition to such a government that existed within the hierarchy of the state. As soon as Corbyn won the Labour leadership for the first time in 2015 an anonymous army General carefully leaked comments to the press regarding the army high command being prepared to refuse to obey any orders issued by such a government. This would not even be the first time that military figures would have entered into a conspiracy, even the right wing Labour government led by Harold Wilson was the subject of coup plots involving Lord Mountbatten and other senior figures from the military and intelligence agencies. The fear of these pillars of the British establishment back then was of rising working class militancy in the face of the onset of a deep crisis of capitalism. The later 1960s saw the Wilson government try to pass the costs of this crisis onto the working class but a series of militant actions began to take place including in the Yorkshire coalfields led by the later National Union of Mineworkers President Arthur Scargill in defiance of the right wing leadership of the NUM at the time. Prior to that there had been the 1966 strike of shipping workers which had been led by a young working class radical known as “John Prescott” (whatever happened to him). These struggles, often powered by the rank and file of the NUM, NUS and other unions. As the governments own statistics show the number of working days lost to strike action started to dramatically increase at the end of the 1960s this led to the Wilson government to try and pass legislation to force state regulation on industrial disputes. This document was known as “In Place Of Strife” and was pushed by the noted “leftwinger” Barbara Castle and was defeated thanks to rank and file pressure upon the union leaders forcing them to tell Wilson that passing the legislation would cause more problems than it would solve. It was not because Wilson was some kind of radical leftist or closet revolutionary that prompted the likes of Mountbatten to plot against him. It was because the likes of Mountbatten and the Generals of the modern era are such extreme reactionaries that they regard anything less than the brutal crushing of all working class resistance as tantamount to communism.

At this point we have to note that the response of the military leaders in Britain is no accident or just the product of the reactionary outlook of the individuals involved it is part of the nature of the capitalist state. As Friedrich Engels argued.

The state is, therefore, by no means a power forced on society from without; just as little is it ’the reality of the ethical idea’, ’the image and reality of reason’, as Hegel maintains. Rather, it is a product of society at a certain stage of development; it is the admission that this society has become entangled in an insoluble contradiction with itself, that it has split into irreconcilable antagonisms which it is powerless to dispel. But in order that these antagonisms, these classes with conflicting economic interests, might not consume themselves and society in fruitless struggle, it became necessary to have a power, seemingly standing above society, that would alleviate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of ’order’; and this power, arisen out of society but placing itself above it, and alienating itself more and more from it, is the state.

Engels – Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

Engels noted that the state originates when human societies first divided into classes that owned and controlled the economy and those who worked. Those with wealth and those without it. The state is the creation of a need to manage the class contradictions between the owning classes (slave owners, feudal lords, capitalists) and those who labour for them. It is built and maintained by members of the ruling class in each historical period, in our time it is built and maintained by the capitalist class. When writing about the nature of the capitalist state Lenin observed.

It is impossible because civilised society is split into antagonistic, and, moreover, irreconcilably antagonistic classes, whose “self-acting” arming would lead to an armed struggle between them. A state arises, a special power is created, special bodies of armed men, and every revolution, by destroying the state apparatus, shows us the naked class struggle, clearly shows us how the ruling class strives to restore the special bodies of armed men which serve it, and how the oppressed class strives to create a new organisation of this kind, capable of serving the exploited instead of the exploiters.

Lenin – The State and Revolution

What Lenin is referring to when he writes of “special bodies of armed men” is the armed institutions of the state. This means the armed forces, police and other agencies of the state who are licensed by the state to use deadly force. The military hierarchy in every capitalist country is drawn from the capitalist class or those very close to them in terms of wealth. This is of course deliberate as the capitalist class requires people who are of a similar class position as themselves to run the armed forces, it is perfectly natural for them to want their own men in these positions. Of course the kind of mentality this breeds in the military hierarchy tends to be extremely reactionary, they are representatives of their class and their job (in recent years) is to prosecute imperialist wars in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and (covertly) against Russia in Ukraine. For such men even a mild social democrat such as Corbyn with his pacifist objections to these wars would be regarded as too much.

We have a clear indication from the forces of the state that they would regard a Corbyn led government as “illegitimate” and would rebel against it, as they have plotted to do in the past. What other responses could we expect from the ruling class? The most potent weapon in their hands is of course the British economy itself. The capitalist class are able to trigger market panics, capital flights and a variety of other events that can destabilise British capitalism. Even a Tory leader who isn’t completely to the liking of the capitalist class can be subject to a destabilisation campaign as the clueless Liz Truss was. The British economy now is so heavily financialised and laden with debt that any disruption, or the hint of it, can trigger a market panic. We can look at the fall of Truss to see a very small amount of what the ruling class can unleash if they choose to do so. Truss immediately ran into opposition from the political establishment and this prompted the Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey to make a series of statements in opposition to the Truss governments economic policies. This came along with a market panic that was then amplified by a mainly anti-Truss media which in turn created panic in the ranks of Tory MP’s who were then told that the answer to this was get rid of Truss and appoint the ruling class’s favoured candidate the former banker, Rishi Sunak. This was all done inside a few weeks and it was a very useful demonstration of how the ruling class can manufacture the removal of a political leader who they deem “unsound”.

The same thing would have been done to Corbyn but with even greater ferocity. The same market crash, statements by the Governor of the Bank of England, screaming headlines in the media and open plotting by Labour MP’s the replace Corbyn. All this would have occurred as soon as the election result had been declared. The question then must be asked if Corbyn and his supporters would have been capable of mounting any kind of fightback against this? Some on the British left would certainly have tried to mobilise against the forces who plotted to remove Corbyn but would they have been able to succeed? At this point it is worth reminding ourselves of the one period in modern British history where some reforms were granted, between 1945 and 1951 under the Labour government of Clement Atlee. What produced these reforms was a combination of the pressure of working class militancy in Britain itself, the radicalisation of even large sections of the middle class during the war years and the inspiration provided to the working class by successful example of socialism in action in the USSR. All of that was required to create immense pressure upon the British ruling class who (wisely) calculated that it was better to accept some reforms than risk a revolution.

Now let us compare this situation to the conditions of 2017. The trade union movement was a pale shadow of what it had been in the post war era, the level of strike in the 2010s though it had increased was still at a very low level, there was no revolutionary nation such as the USSR which could inspire the working class and create fear within the capitalists. A Corbyn government would face a unified ruling class and political establishment and unlike in 1945 there wasn’t even the existence of a small but significant Communist Party which could pressure a reformist government by mobilising workers in support of reforms and pushing it to go further. Then there is the question of whether Corbyn and his supporters were prepared to actually take the only route that could have caused the ruling class to be more cautious in their assault, to call upon the British working class directly to mobilise in support of such a government. Corbyn never made any appeals such as that during his time as Labour leader. Even when the 2016 coup was starting it was activists in the grass roots who organised the pro-Corbyn demonstrations, the man himself did not. Corbyn also surrendered meekly on issue after issue when under pressure from his opponents within the party, from the phoney “anti-semitism” scandal to mandatory reselection to Brexit he capitulated quietly every single time. He abandoned several of his key political allies to witch hunts when a hostile bourgeois press demanded it of him and the Labour left (led by the craven John McDonnell) proved absolutely no better at standing up to political pressure than Corbyn himself did.

The trade union leaders of the time were absolutely no better in terms of their willingness to engage in a difficult battle with the ruling class. Though the likes of Len Mcluskey backed Corbyn they were not interested in the kind of mass strikes and mobilisations that would have been necessary if even the mildest of reforms was to be forced through. As other CCP comrades have noted in many articles, the union leaders in this country have been and remain establishment figures who are far more likely to sell out to the ruling class than to wage a real struggle. This is why men like Arthur Scargill and Bob Crow stand out, because they are so rare. Men like Len Mcluskey talk a good game but talk is all it turns out to be in most cases.

To return to the original question here, what if Corbyn had won in 2017? The answer is that there would have been a crisis instigated by the ruling class from day one. The army chiefs and intelligence agencies would have openly plotted against the him, the capitalist class would create a panic in the markets threatening economic collapse and the capitalist media would have waged a non-stop campaign to create an ever greater sense of crisis. The media would create an endless sense of unfolding disaster, Corbyn’s enemies inside the Labour Party would seize the opportunity to claim that “Jeremy must go” in order to “restore confidence” and the left in the labour party would complain, whinge and then capitulate. Corbyn’s only chance at preserving his premiership would have been to try and rally the working class and create a countervailing pressure upon the ruling class in such a way as to at least cause them to worry about the situation moving in a revolutionary direction. Corbyn though is not that radical or that daring, nor were his allies, nor did the capacity exist within the wider left to take on such a huge task. The reality is that Corbyn would have surrendered and been replaced within a few months and his allies would complain but offer no resistance.

As noted above though there are ways in which workers can force the ruling class back but that takes organisation and determined leadership. Mass walkouts, workplace occupations, disruption of the capitalist class’s ability generate profit. All of these are within the power of the British working class to carry out but to do so would take a higher level of class consciousness than that which existed in 2017 and now. These are not impossible tasks, our class has shown great strength when unified and determined to take action beforehand as shown by the struggles of the later 1960s and early 1970s. Successful struggles can be waged but not with the leadership of the unions as it is and not with the pusillanimous labour left in charge either.

Leave a comment