Between 1945 and 1951, the Labour government saw the future of housing policy and the relief of the problems of inner-city areas in terms of a major development in what at the time were called ‘new towns’. This policy was reversed in 1951 when the Conservative government came into office. Instead of new towns being developed, there was instead an increased emphasis on the clearance of slums in the inner cities. The prevailing theory at the time was that the only way to achieve this aim was to build flats at a very high density.

The construction industry welcomed the proposal and moved into system building. The larger firms in the construction industry developed some very healthy business in producing the major housing works in the inner-city areas.

The problems with high rise blocks were particularly exacerbated by the Housing Subsidies Act 1956, which gave a higher subsidy for flats the higher they were built. That provision, along with system building by the construction industry which enabled lower-skilled workers, at lower wages, to complete the work, resulted in the proliferation of high-rise blocks and tower blocks in many inner-city areas across the country.

In 1967, under a Labour government, a new subsidy system was introduced which took away the incentive to build tower blocks at the height that they were being built previously. In 1968 the Ronan Point disaster began to make people think about whether we ought to be developing our towns and cities in this way.

RONAN POINT

Ronan Point was a 22-story tower block in Canning Town in Newham, East London which partially collapsed on 16th May 1968, having been open for only two months. The collapse was caused by a gas explosion which blew out some load bearing walls, causing the collapse of one entire corner of the building. The tower was built at a cost of just £500,000 by Taylor-Woodrow Anglian using a technique known as ‘large panel system building’, which involves casting large concrete pre-fabricated sections off-site and then bolting them together on-site to construct the building. The pre-cast system used was known as the Danish Larsen & Nielsen system. The failure was caused by both poor design and poor construction, which led to major changes in British building regulations. In the early 1970s, every building worker had heard of Ronan Point and the stricter methods of working practice that ensued from that disaster. More steel bars and rods in each floor and wall joint were required, as well as mandatory inspections carried out by the building’s Clerk of the Works before any concreting could be carried out. These extra steps slowed down the construction process considerably.

The Social Housing Action Campaign (SHAC) has called for more information to be provided by housing associations on any potential problems regarding RAAC. They said:

“It is possible that RAAC is present in housing association homes, particularly tower blocks, but as yet no information has been published either by landlords or their representative body the National Housing Federation”

Unlike public bodies, housing associations are not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, so just because Steve McSorley, who is the director of the structural engineering consultancy Perega, has said that RAAC was less likely to be prevalent in 1960s tower blocks because “it was rarely used in anything more than three storeys high, but its possible it will be found in some roofs”, there is no reason to accept what he says.

This has been about pre-cast concrete housing from the 1960s and 1970s, which may or may not contain RAAC, but Chapter 2 will be about its confirmed use in schools, hospitals and public buildings and the devastating effects of it.

The decision to close all English school buildings that potentially contain RAAC has caused a political storm across the country and, whilst fewer than 1% of schools and colleges are affected, the possibility that other public buildings including hospitals, courts and prisons may contain RAAC has led the Labour Party to accuse the Tories of presiding over a decade of austerity-driven neglect of public infrastructure.

What is RAAC?

Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete is a lightweight alternative to traditional reinforced concrete, with good fire resistance and thermal insulation properties.

It was mainly used between the 1960s and 1980s to make roof planks and walls. Its flaws, including a vulnerability to water seepage, have been known for decades. In 1999 the Standing Committee on Structural Safety (SCOSS), an expert group, issued warnings about its use. SCOSS warned that “pre-1980 RAAC planks are now past their expected service life and it is recommended that consideration is given to their replacement”.

The problems were compounded by the Tory austerity policies in the 2010s, but its roots go back decades, as in many parts of Europe, post war reconstruction, baby booms and expansion of the welfare state drove a surge in public investment in Britain through until the 1970s, often using cheap but limited-life materials such as RAAC, with the attitude of ‘build it quick, build it cheap’, which suited the building firms, British councils and governments of all persuasions.

Following the post-war boom, state spending dropped in most countries, but the drop in spending in Britain after Thatcher’s Tory government came to power in 1979 was sharper than most.

Though Blair’s Labour government began to rebuild capital spending, a study last year found that long-term average net public investment dropped from 4.5% of GDP in 1948- 1978 to 1.5% in 1979-2019. Even under New Labour, Britain’s investment share was smaller than the OECD average or most G7 peers.

Deteriorating post-war infrastructure is far from being just a UK problem, but the RAAC affair highlights that, whichever party wins the next election, they must find funds not just to boost day-to-day public spending, but to revive capital investment as well.

It is plain that both parties have been failing in their duty to people, but it seems that the Tories have been the bigger culprits.

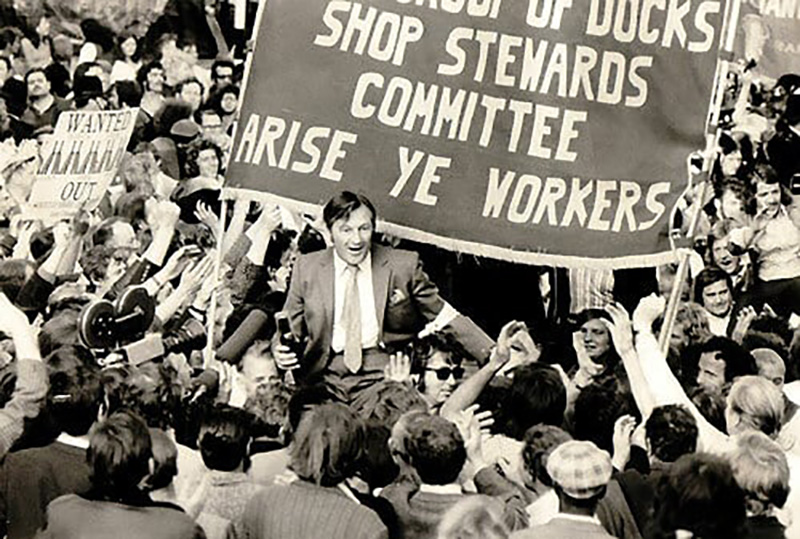

In conclusion, both parties have shown themselves time and time again to not be parties of the working class, as evidenced by things like the slipshod and care-free methods they oversaw in the construction of schools, flats and hospitals in post-war working class communities. It’s also evidenced in their approach to the problems of RAAC when the problems with it became clear decades ago.

As always, they are just conforming to type.

Leave a comment