British news media, having broadcast propaganda on the mass slaughter of Palestinians on behalf of Israel and US imperialism for the last seven weeks, became temporarily distracted by the literally explosive events in Dublin which unfolded on the night of Thursday 23rd November.

According to the news media, the riots were precipitated by a violent attack which took place earlier in the day, when three children and a teaching assistant were injured in a stabbing outside a school. The Garda issued a statement on the incident, which included that the attack “does not appear to have a terrorist motive”. It was this turn of phrase which is thought to have led many in the city to make the leap, either by themselves or with the assistance of far-right agitation, to conclude that the school attack was carried out by a non-white immigrant.

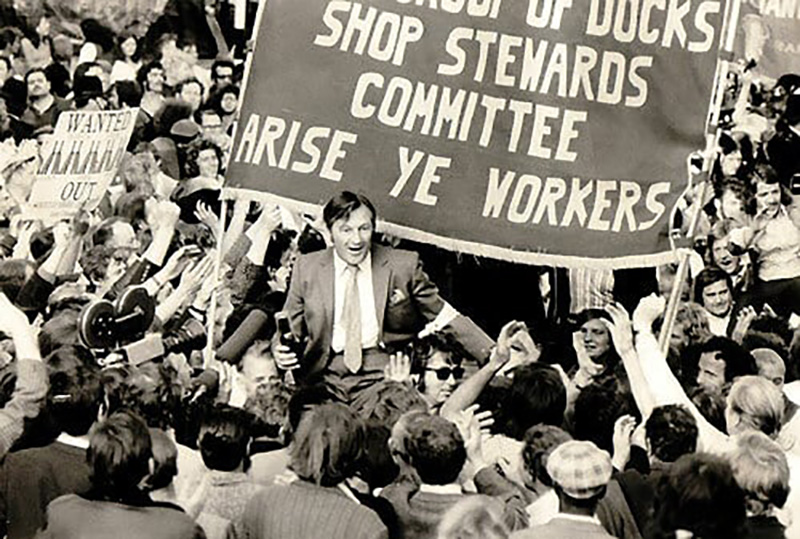

What followed was the biggest civil disturbance in the city in decades and the biggest single mobilisation of the Garda in the history of the Irish republic. The Irish Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, said that some 500 people took part in the rioting, as vehicles were set ablaze and shops were looted, while the chief of police Drew Harris blamed ‘far-right ideology’ for the explosion in violence.

We have written on the potentially explosive consequences of immigration in our article The Immigration Question, part of which examined the riots which took place in Knowsley in Merseyside in February 2023. There are some glaring similarities between the riots which took place in Knowsley and those which consumed Dublin City Centre on the night of 23rd November – both were precipitated by attacks on locals: In Knowsley it was the harassment of a young girl, in Dublin it was the stabbing of three children and an adult. Both attacks were alleged by some in the area to have been perpetrated by an immigrant and both localities have been targeted by far-right groupings, seeing fertile ground to sow racially-aggravated agitation in poor working class areas long since abandoned to their fate by the ruling class.

Anti-immigration protests began to surface in Ireland as far back as November 2022, while the country attempted to settle some 65,000 refugees. Protests continued across the country, but came to prominence earlier this year when thousands took to the streets of Dublin claiming that ‘Ireland is Full’. Clearly the events of 23rd November, whilst spontaneous, were not a discrete event, rather part of a pattern of protests based in deep resentment which goes back for over a year.

As we wrote in our article on immigration, the ruling class are deeply cynical in the way in which they treat immigrants and refugees, often placing them in poor working class areas whose local services are already stretched to breaking point, if they exist at all after years of crushing austerity. Whilst it is true that right-wing agitation has played a key role in the fomenting of tensions, these agitators have been afforded every opportunity by the ruling class to do so, using already existing and deep-seated social and municipal issues and creating division and anger – anger which has manifested itself on the streets of Dublin and other Irish towns and cities over the last twelve months.

The Irish ruling class arguably has a deeper crisis within its borders to contend with than the British ruling class – not only does it suffer with a declining birth rate in common with Britain, it also has a culture of emigration which goes back as far as the 19th century, due to a great degree by a British ruling class, which treated the island of Ireland during this period as little more than a farm colony, exploiting its land and people for agricultural produce and continuing to exploit that land during The Great Famine of 1845 to 1852, during which 1 million people died and another 2 million were forced to leave the country. There were 8 million people living in Ireland in 1840. Today it is 7 million, as clear a sign as could be seen that the effects of The Great Famine persist to this very day.

Even the independence that the Irish won from Britain in 1922, with its constitution as a republic in 1937 and its formal declaration of the same in 1949, could not ease the plight of its people. The chief reason for this is that Ireland did not and has never fully won full independence from Britain. Only 26 counties of the island of Ireland won independence, with six remaining as a British-run statelet in the north. With those six counties being amongst the most industrially-developed and economically powerful, Ireland’s full political, industrial and economic development was severely hamstrung in the years since independence.

Further to this, the fact that Ireland was unable to win full socialist independence from Britain meant that, as James Connolly said:

“If you remove the English Army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic, your efforts will be in vain. England will still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs.”

The Irish ruling class, faced with these impediments to develop its industrial and economic base, chose in the mid-1990s to fully embrace the imperialist trading bloc that is the European Union, as well as adopt what became known as its ‘Celtic Tiger’ economic policy, which in essence was to slash Corporate Tax in order to tempt multinationals like Google and Apple to its shores, as well as to dive headlong into property speculation. Coupled with this, the Irish ruling class attempted to solve its aforementioned problems of low birth rate and emigration by importing workers from abroad, namely the former socialist eastern bloc states, who were well educated, spoke English and, vitally, were willing and able to work for lower wages than the Irish population could.

After a period of sustained growth in GDP, the Celtic Tiger showed itself to be, in reality, a paper one, when the financial crash of 2008 left dozens of developments abandoned unfinished, the economy of Ireland plunged into a deep recession and, with no currency of its own (the Euro is in effect a foreign currency), it was left at the complete mercy of the European Union and the European Central Bank, with Germany as its hegemonic member. Ireland became one of the ‘PIIGS’ – Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain – five weaker European economies which the powerful states in the north of Europe, which at the time included Britain, believed were basket cases who created the terrible financial messes that they found themselves in.

All of this is the backdrop against which the events which unfolded in Dublin on 23rd November must be assessed. Ireland has never fully economically developed in its post-colonial era, partly because it remained under the boot heel of British imperialism, partly because it chose to place itself under the boot heel of European Union imperialism and partly because it failed to fully liberate all 32 counties in a single, unified, socialist state with a planned economy and a working class owning and controlling the means of production.

The Irish left, lacking either the inclination or ability to apply a class-based analysis to the problem, has dismissed those involved in the disturbances as racist lumpens who have seized on the opportunity for wanton violence and looting based on the loosest of premises, that of a violent attack on three children and an adult outside a school. However, this position opts to ignore that fact that a sizeable proportion of those taking part in the disturbances seen in Dublin on 23rd November are very angry and mostly young people driven to violence by what they perceive as a system which has failed them and placed them at the very bottom of the list of priorities for their elected rulers.

The left would far rather label these people as irredeemable racists for a number of reasons: They have no answers for the concerns that they have, including why there is a persistent shortage of affordable housing or decent jobs, why people who settle in their country are placed in areas least able to support them and why there seems to be neither the inclination or ability of Ireland’s rulers to change this. This marginalisation and refusal by the left to engage with people, rightly angry about the decades-long decline of their neighbourhoods, concedes the opportunity to engage to far-right extremists, who are only too happy to talk to them with their versions of why their communities have regressed in the way that they have.

We must both reject and resist any far-right agitation in poor working class areas – they fail to offer people in poor working-class communities the real answers to their legitimate concerns and seek only to sow division and hatred among an already angry and marginalised group. Instead, we need to face their concerns head-on: We must be prepared to hear views that we may not like, but be prepared to both listen and to challenge them with our own arguments as why the world is the way it is and why working class people, whether they were born here or arrived as immigrants, are placed at the very bottom of the pile by our ruling class.

For Ireland, the only solution to the issues that beset the country and have beset it since the 19th century is for it to become a fully unified, independent and socialist state.

Leave a comment