The news that the FA Cup, the oldest football competition in the world, will be hidden behind a paywall for the first time in its history is yet another nail in the coffin of what was once the most revered football competition in the world. The tournament of Ricky Villa’s magical goal against Manchester City in the 1981 Final replay, non-league Hereford’s incredible win over Newcastle in 1972, Sutton United dumping Coventry City out of the competition in 1989 and George Best scoring six goals for Manchester United in their FA Cup tie against Northampton Town in 1970 would be restricted to only those willing and able to afford to pay out to watch it.

Starting with the 2025/26 season, TNT Sports, a channel which currently costs subscribers £30.99 per month, will have exclusive rights to broadcast all FA Cup games. The final, which is protected under legislation, will still be broadcast on a ‘free to air’ channel, and TNT have pledged to allow other selected games to be shown on free to air channels, but every other match will be concealed behind a prohibitively expensive paywall. For those who already pay Sky Sports for their Premier League and Championship football coverage, playing another £30.99 for the FA Cup will be a fee too far when the price of living has skyrocketed and working class people are already considering whether to continue with television subscriptions and streaming services which they rarely use.

In an interview on the ‘Quickly Kevin; Will He Score?’ podcast in April 2017, broadcaster (and all-round legend) Jim Rosenthal discussed his career options when both Sky and British Satellite Broadcasting launched their respective channels and that he had been offered what he described as “silly money” to move to BSB, but never really gave the offer serious consideration because, in his words, he would be taking “money to disappear”. In its deal with TNT Sports, the FA Cup has decided to take money to disappear from the TV screens of viewers, but this is only one of a number of changes to the competition – some within its control, others not – which has has contributed to the FA Cup’s continued decline and slide into irrelevance.

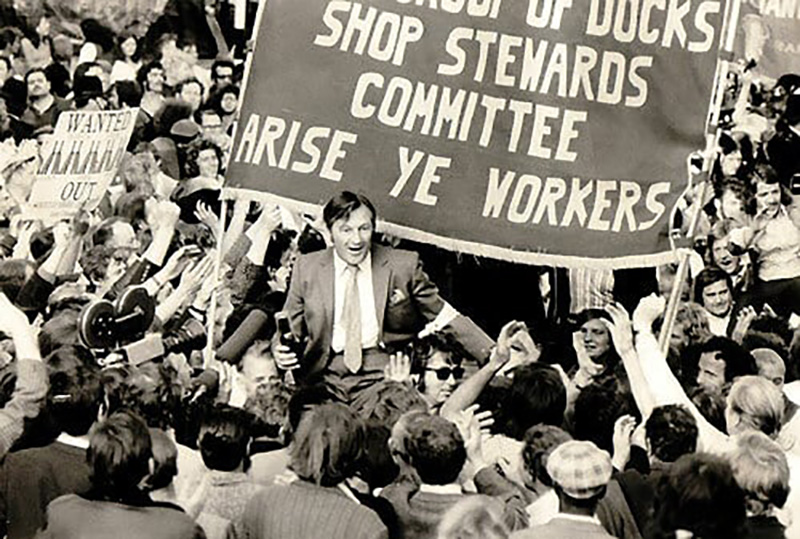

It’s difficult to assess the decline of the FA Cup without becoming incredibly nostalgic about what the competition once was. The FA Cup was first played in the 1871-72 season and was won by Wanderers, a team founded in Leytonstone (then Essex, now east London), who beat Royal Engineers 1-0 in the final which was played at the Kennington Oval. Wanderers, so called because they didn’t have a home ground of their own, went on to win the competition another four times. The competition grew in size and interest during the following decades to the point where it became a national institution – the FA Cup Final often became the quietest day in the calendar for anyone venturing outside their homes as millions of people, even those with barely a passing interest in the sport of football, would settle down to watch the final.

The first televised FA Cup final was broadcast in 1938. There were only 10,000 television sets in the entire country at that time, so the match was actually watched by more people in the ground than it was by those watching in their homes. But this changed dramatically over the following decades. The FA Cup eventually became an all-day televised event – both BBC and ITV would devote hours of coverage to the pre-match build-up, interspersing their broadcasts with sections on fans travelling up (or down) to Wembley Stadium, interviews with players and staff ahead of the game and, of course, lots of highlights of previous rounds of the competition. It’s little wonder that, for most football players and managers, winning the FA Cup was the pinnacle of any career – the final was a showpiece match, separate from any other football, with its own dedicated day in the calendar and venue. As a kid, I seem to remember the weather always being sunny on Cup Final day.

But the game of football was evolving as football entered the 1990s, and with it was the format of the FA Cup. Changes to the competition made by the FA itself began erode the special nature of the Cup and turn it from a prestigious and distinctly unique tournament to one which was devalued and, in the case of some clubs, an inconvenience.

One of the first retrograde changes to the FA Cup was the abolition of ‘endless’ replays. Until 1989-1990 season, drawn ties would be replayed, with the away team in the original round playing as host in the replay. This would continue, with host team alternating with each replay, until a team emerged victorious. A fourth qualifying round tie between Alvechurch and Oxford City in 1971-72 season required five replays to determine the winner. Replays were often played three or four days after the original tie, but from the 1991-92 season were then scheduled ten or so days after the original tie at the request of the police, which meant that ‘endless’ replays could become a scheduling nightmare.

It was for this reason that the FA introduced extra time and penalty shoot-outs at replays. In 1998 they scrapped FA Cup Final replays and semi-finals would go to extra time if the two sides were drawn at 90 minutes, but would still go to a replay if the two teams were tied at 120 minutes. However, the FA then made another retrograde step when they scrapped semi-final replays entirely, with the last semi-final replay arguably being one of the greatest ever, when Manchester United beat Arsenal 2-1 on 14th April 1999, with Roy Keane sent off, Peter Schmiechel saving a penalty from Dennis Bergkamp in the dying seconds of normal time and Ryan Giggs, in the 109th minute and having collected the ball from just inside his own half, ran at Arsenal’s defence before smashing the ball high beyond the despairing dive of David Seaman to send Manchester United through to the final.

As someone who watched that incredible replay in a pub in Chelmsford in Essex, I wondered if abolishing semi-final replays was really a good idea after all. The competition had already been eroded by the abolition of endless replays, then the FA Cup Final replay, and the power and wealth of the Premier League had begun to eclipse the ‘magic’ of the FA Cup. But even then I could not have anticipated just how far the FA Cup would slip from being the showpiece tournament it was into the shell of a competition it came to be.

The tournament was already sponsored by the time of Manchester United’s incredible FA Cup semi-final replay, having been called The FA Cup Sponsored by Littlewoods since 1994. I wasn’t ever an advocate of sponsorship: I didn’t even like Coronation Street being sponsored. I always felt that the FA Cup was special and that sponsorship somehow damaged the ‘specialness’ of the tournament. Of course, that ‘specialness’ came from lots of things other than whether or not the tournament was sponsored, including the build-up to the match through the course of the morning and early afternoon, as well as the singing of ‘Abide With Me’, the semi-official hymn of the FA Cup, which, even as someone without any religious affinity, is a hymn with which moves me whenever I hear it. I remember vividly Elton John singing the hymn through his tears as his beloved Watford appeared in the FA Cup Final in 1984.

The Final would, at least as far as I was concerned, always kick off at 3.00pm on a Saturday. Certainly the history of the tournament backs up my view – the match had been kicking off at 3.00pm on a Saturday since 1903. That was until 2011, when the FA decided that the Cup Final would kick off at 5.15pm, apparently at the behest of the TV companies who had paid considerable sums of money for the privilege of dictating to the FA and football-loving public when the Final could take place.

For the them, the advertising revenue was higher with a tea-time kick-off than it was for its traditional 3.00pm start. It was yet another change, not necessarily a devastating one in and of itself, but part of a series of changes going back over thirty years which had severely damaged the FA Cup as a competition and a national institution. This was not isolated to the Final, either. Traditionally each round would kick-off at 3.00pm on a Saturday. As TV companies and the BBC demanded greater and greater return for the money they invested, selected matches were moved to Sundays to be broadcast live, then other matches started to be re-scheduled to start before or after the legally locked times of 2.45pm to 5.15pm on Saturdays – I attended a FA Cup 4th round match between Tottenham Hotspur and Wimbledon at White Hart Lane on February 13th 1993 which kicked off at 11.45am, shown live on Sky.

In 2016, Exeter City entertained Liverpool in the 3rd round of the cup at St James Park. It was determined that the match should kick-off at 7.55pm on Friday 8th January. Liverpool fans travelling to the match by train would have been disappointed to find out that the last train which could have got them back to Liverpool departed Exeter St Davids station about fifteen minutes after the match kicked off. The journey by car would take a little less than five hours. Neither the FA nor the broadcasters gives a stuff about football fans, particularly when it comes to scheduling FA Cup matches, which are now scheduled across up to a five day period over each weekend the tournament is played. The fifth round of this year’s competition is being played on a Tuesday and Wednesday evening, evidence of how little value the competition holds to either Premier League or Championship clubs.

The Premier League has done irreparable damage to the FA Cup. For clubs in the late 20th and early 21st century, income has become the first and only consideration – they had no desire to see Champions League qualification possibly jeopardised by FA Cup replays and, certainly in the cases of Premier League clubs in the lower reaches of the table, when forced to decide between an FA Cup run and Premier League survival often opted for the more lucrative latter option. Indeed, with the prize money offered by the FA Cup, a Premier League club could make more money by finishing 13th in the Premier League and be knocked out of the Cup in the 3rd round than by finishing 15th in the league and winning the FA Cup. The riches of the Premier League means that there is a huge strata of clubs – from the bottom section of the Premier League down to the top section of the Championship – for whom a good run in the FA Cup is not a priority. In fact the FA Cup could either potentially jeopardise a club’s Premier League survival or potentially damage a promotion run into the Premier League.

The FA didn’t help their own competition by allowing Manchester United to opt out of it in 2000 when they were part of a consortium of parties who were attempting to bring the 2006 World Cup to England for the first time since 1966. The FA, aware that an English club participating in FIFA’s fledgling Club World Championship may add some much needed gravitas to the tournament (Manchester United were the English and European champions at the time) and be a good PR move for a nation bidding to host the World Cup. Manchester United, on the other hand, knew that they had leverage – its arguable that they had little interest in committing to a club competition taking place in January, smack-bang in the middle of the domestic season, and in Brazil, some 5,800 miles away. The FA allowed Manchester United to drop out of the FA Cup: A move that angered football fans already concerned by the continued erosion of the tournament, mainly by the FA themselves. It’s fair to say that the tournament was not dealt a death-blow by this decision, but it gave clubs who had fielded their reserves in a 3rd round FA Cup tie because there was a league six-pointer scheduled a week later the ammunition they needed to defend themselves.

The FA Cup has suffered a death by a thousand little, and in themself insignificant, cuts. From the abolition of endless replays, to the scrapping of Final and then Semi-Final replays, to moving the kick-off to the early evening and then back to 3.00pm and, critically, being at least a secondary consideration for teams in the bottom half of the Premier League or the top section of the Championship, the FA Cup has become a pale imitation of the once great competition it once was. The TNT Sports deal will not enhance the FA Cup, nor will it dispel the belief held amongst many football fans that the FA Cup, and the game of football itself, has been irreparably damaged by the pursuit of profit over the beautiful game.

Leave a comment