Netflix’s Latest Liberal Mind Rot

The new British Netflix programme that everyone’s talking about, Adolescence, has even won the public endorsement of Labour Party Prime Minister Keir Starmer. He was apparently so moved by the show that he posted about it twice on X (formerly known as Twitter). In one of those posts, he claimed the programme “hit home” for him as a father of two, and backed plans for Netflix to show the series “free” in schools. In the other, he praised conversations he’d had with charities about the issues raised.

The show centres on a young boy called Jamie and his family. It opens with a dramatic police raid on the Miller household, dragging 13-year-old Jamie off to a police station. There, during a recorded interview, police show Jamie and his father CCTV footage of Jamie stabbing a young girl multiple times, resulting in her death. The brutality of the crime jars against the image of a frightened, seemingly normal child and a supposedly stable family. This contrast is clearly engineered for dramatic effect: the boy next door who turns into a killer.

The next episode follows two detectives investigating the crime. Most of this plays out at Jamie’s school, where it’s revealed that the environment is rife with cyberbullying. Jamie, we’re told, was one of its victims. The writers then take a bizarre turn, dragging in the term “incel” (involuntary celibate) as if this is a word being thrown around the playground. Frankly, I found this absurd. To describe 13-year-old boys as incels is not only creepy, it’s completely detached from reality. I remember school well enough to know teenage sexuality exists, but there was never any expectation for boys of that age to have “lost their virginity”. Even official statistics reflect that—just 19% of teenagers report having sex before the legal age of 16.

So, what’s the real focus here? Ostensibly, it’s cyberbullying. But the introduction of incel rhetoric is a clear set-up for what’s coming in episode three.

Seven months have passed, and Jamie is now held in a youth detention centre. We watch him undergo a psychological assessment with a cold, middle-class female psychologist. By this point, Jamie appears to have completely changed character. Either he’s undergone a massive personality shift or, more likely, the writers want us to believe he was harbouring the mindset of a misogynistic adult all along. Gone is the frightened boy. In his place, a miniature bigot.

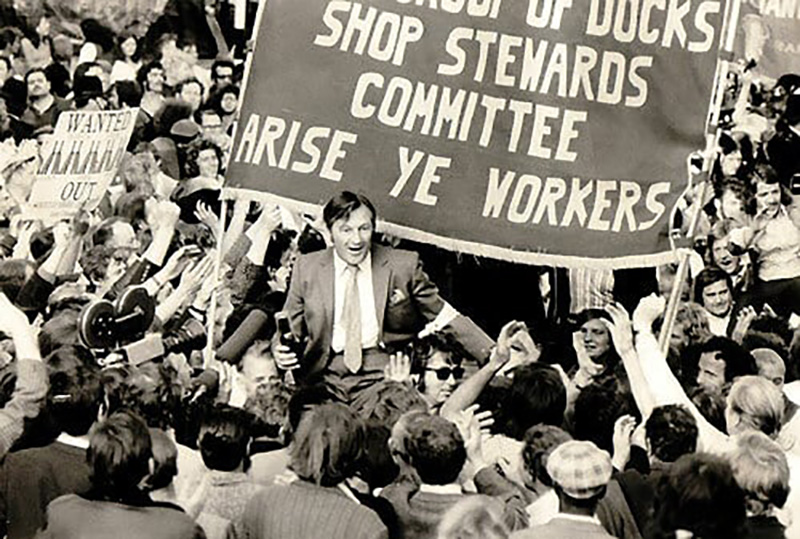

The agenda becomes blatantly obvious in this episode: the demonisation of so-called “toxic masculinity.” This had already been hinted at with the incel playground nonsense, but now it’s front and centre. As per usual with liberal media, class, poverty, or systemic abandonment are completely ignored.

Jamie’s family live in a tidy house, and while there’s a nod to the struggles of working life, the show never once mentions the non-stop attack on working class communities for over 50 years leading to multiple generations growing up hopelessly alienated. Jamie isn’t shown as a product of economic collapse or social fragmentation, he’s just a “damaged” boy poisoned by masculinity. His community isn’t crushed by capitalism, it’s merely “troubled” by culture. His actions aren’t politicised—they’re pathologised.

This is the standard liberal manoeuvre: strip class from the equation and you can repackage social crisis as a morality tale. The contradictions of capitalism become individual pathologies. The working-class boy is no longer a product of political economy, he’s reduced to a clinical subject, to be examined, corrected, and ultimately contained. His suffering is depoliticised, his fate preordained, not by class struggle, but by institutional management.

The final episode returns to Jamie’s family. It’s his father’s birthday, and they’re trying to return to some kind of normality. That attempt is ruined by a group of teenagers defacing his work van. En route to clean it up, they receive a call from Jamie saying he’s decided to plead guilty. The parents return home, trying to come to terms with his decision. Once again, the cause is pinned on this phantom called “toxic masculinity” and the online radicalisation of children into misogyny.

In all honesty, I find this miniseries deeply dishonest. Stephen Graham, who plays Jamie’s father, has starred in some genuinely strong films; Gangs of New York, Snatch, This is England. But more recently, his roles have become increasingly politicised in the worst kind of liberal way. Help dealt with COVID-era nursing. Little Boy Blue recounted the tragic murder of Rhys Jones in 2007. But The Walk-In may have been the worst of the lot—tying Brexit to a surge in far-right activism, with Graham cast as a campaigner for Hope Not Hate. At this rate, he’s one Ukrainian flag away from being Britain’s Sean Penn.

Conclusion: Manufacturing Morality, Obscuring Class

What Adolescence really offers is a carefully manufactured moral panic, a slick, sanitised narrative that pretends to care about working-class boys while throwing them under the ideological bus. Its critique never points upwards, only sideways. Its villains are other poor boys. Its solution? More surveillance, more school “interventions,” and more state-led reprogramming, anything but empowering the workers with a class awareness.

“Toxic masculinity” is a nonsense term. It doesn’t describe a class. It doesn’t describe a system. It describes a vague set of behaviours supposedly unique to men, divorced entirely from the economic conditions that shape those behaviours blamed solely on men. It is the liberal’s comfort blanket: a way to talk about violence, anger, and alienation without ever mentioning capitalism.

Real working-class struggle is not toxic. It is the product of life under a system that crushes solidarity, isolates workers from their communities, robs families of time and dignity, and replaces collective purpose with individual resentment. Until that system is confronted head-on, shows like Adolescence will keep telling us to “fix the boys” while ignoring the conditions that broke them.

Leave a comment