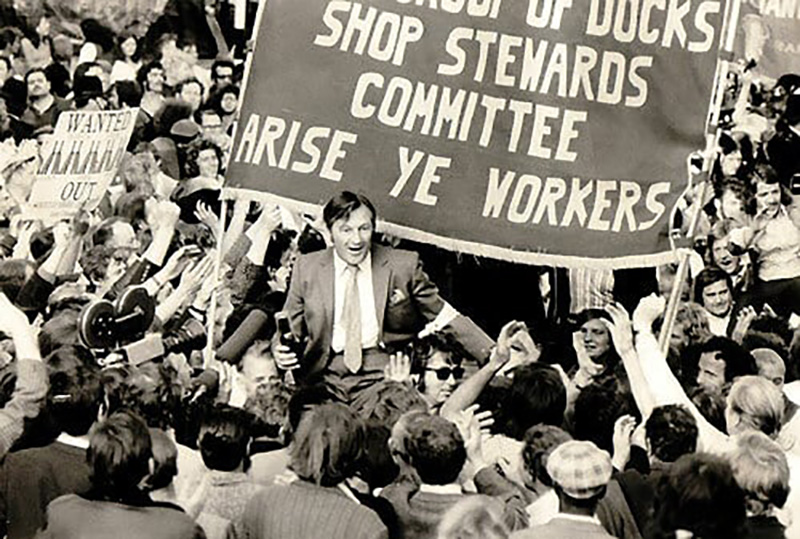

Britain is the oldest capitalist nation, and the oldest imperialist nation, in the world. As it industrialised first and most comprehensively it created gigantic class conflicts between the early proletariat and the capitalist class as the jobs of artisan workers (such as weavers) were destroyed and these workers forced into the growing industrial cities like Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Birmingham. The class struggle between worker and capitalist is a modern version of the oldest struggle of all, between those who own the means of production and those who have to work using them. The class struggle in the capitalist era takes on a new form, that of the industrial worker against the capitalist and it necessitates a new form of organisation in order that the worker can hope to take back some of the immense profits their labour has generated. Trade unionism is the first crucial step on the road to the working class achieving higher levels of class consciousness. In taking part in trade union battles workers learn certain basic, but fundamental, lessons about their interests being in conflict with those who own and control their workplaces. They learn vital lessons about the potential power of collective organisation and how, when the working class acts as one, they can force even the richest and most powerful capitalists to back down. We at the Class Consciousness Project do not underestimate the role that trade unionism can play in advancing the cause of working class liberation, but we can see clearly that trade unionism alone is a very limited form of struggle. In this article we will examine the key weaknesses of trade unionism and explain why we analyse things this way.

Trade unionism, by its very nature, accepts the foundational premise of capitalism: the wage-labour relationship. Unions do not organise to abolish the system where one class sells its labour-power to another class that owns the means of production. Instead, they organise to negotiate the price and conditions of that sale. This is a fight within capitalism, not a fight against it. The union’s role becomes that of a collective sales agent for the commodity of labour-power, seeking to secure a better deal in the marketplace. While this can lead to some short-term victories, it leaves the core exploitative dynamic intact. The boss remains the boss, the worker remains the worker, and the extraction of surplus value—the source of profit—continues, albeit potentially at a slightly revised rate.

This acceptance of the system’s logic leads directly to the second major weakness: the tendency towards what we call ‘economism’. This is the reduction of the working-class struggle to purely short term economic demands—higher wages, better benefits, longer breaks. Political questions about state power, the ownership of industry, and the overall direction of society are sidelined or abandoned entirely. This creates a narrow, sectional view of the world. A union’s duty is to its dues-paying members in a specific company or industry, not to the working class as a whole. This fosters what is often termed sectionalism or corporate consciousness—a mindset where workers identify more with their immediate trade or employer than with the broader proletariat.

We see this play out repeatedly. One union may secure a lucrative contract for its members by agreeing to productivity measures that cost jobs elsewhere, or by opposing environmental regulations that threaten their specific industry, even if those regulations benefit the wider community and the planet. The construction worker may see the environmental activist as a threat to their job, rather than a potential ally in a fight for a sustainable future. This fragmentation prevents the development of a unified, revolutionary class consciousness—an understanding that the interests of all workers are fundamentally opposed to those of the capitalist class as a whole, and that their liberation requires a collective political project to seize state power and reorganise society. This has been a problem plaguing the British working class since the earliest days of trade unionism as workers were represented by unions specifically organised around their trades. This is what is known as ‘craft unionism’ and breeds the kind of narrow view that leads to some unions selling out broader struggles to get a deal for their membership. There have been many examples of this over the centuries but a recent one would be the notorious EETPU under the leadership of Eric Hammond who cut a deal with Rupert Murdoch for representation at his new Wapping print plant and sold out the printers unions in the process. Hammond died with an OBE to his name, as is often the case for such leaders who serve the interests of the British ruling class.

The third critical weakness lies in the process of bureaucratisation. To effectively negotiate with sophisticated corporate management, unions necessarily develop a specialised layer of full-time officials: negotiators, lawyers, and administrators. Over time, this bureaucracy develops its own distinct material and social interests. Their status, salaries, and career prospects become tied to the smooth functioning of the union as an institution, which in turn depends on a stable relationship with capital and the state.

This creates a powerful conservative pressure within the union apparatus. The bureaucracy’s interest lies in managing discontent, channeling it into predictable, ritualised forms like scheduled negotiations or official strikes that follow legal guidelines. Wildcat strikes, mass occupations, and other forms of militant, rank-and-file-led action that threaten the union’s recognised status and their relationship with employers are often discouraged or outright suppressed. The goal becomes conflict resolution and contract maintenance, not the escalation of class antagonism. For the bureaucrat, a settled contract—even a rotten one—is often preferable to a victorious but unpredictable struggle that challenges their control. Their role evolves from being leaders of struggle to being managers of the working class, “labour lieutenants of capital,” in the phrase of the early American Communist leader Daniel De Leon.

This dovetails with the fourth weakness: integration into the capitalist state. In most advanced capitalist countries, unions have been granted legal status. This legal recognition, while offering protections, also comes with very heavy strings attached. Labour laws dictate how and when strikes can be called, mandate cooling-off periods, prohibit secondary pickets, and force disputes into state-mediated arbitration. By operating within this legal framework, unions become enforcers of industrial peace. They must police their own members to ensure compliance with the very laws designed to limit the power of labour.

The union becomes a component in the system of capitalist governance, helping to regulate the class struggle and keep it within safe, non-revolutionary bounds. During economic crises, this often leads to unions partnering with employers and the state to impose austerity measures—wage freezes, pension cuts, and layoffs—under the guise of “shared sacrifice” or saving “national competitiveness.” This process demonstrates with brutal clarity how trade unionism, when divorced from a broader political challenge to capitalism, can become a force for disciplining the working class and facilitating the very attacks it was formed to resist. This is especially true in Britain, where we have some of the most restrictive anti union laws in the world. The trade union bureaucracy is responsible for enforcing these laws on its own members and the laws have become a great excuse that the TUC leaders use to excuse their own inertia and repeated capitulations to the ruling class.

Our final point here is that trade unionism is, by its very nature, unable of trade unionism to address the systemic, generalised crises of capitalism. Unions can fight for a larger slice of the pie during periods of economic growth, but they are powerless against the inherent anarchy of the capitalist system itself. When recession hits, inflation soars, or industries are automated away, the purely economic struggle hits a wall. No amount of bargaining can stop a boss from closing a factory deemed insufficiently profitable or prevent a financial crisis triggered by speculative capital.

These crises are not aberrations but endemic features of the mode of production. A movement that limits itself to wage demands has no answer for them. The only real answer is a political one: the seizure of the means of production by the working class to organise production rationally and democratically for human need, not private profit. This requires a revolutionary party and a high degree of class consciousness, not just a trade union. This is why we set up the Class Consciousness Project, our aim is help the working class understand that its not just the bosses and the government they are up against but the conservative bureaucracies in the trade union movement that limit our struggles. These are not insurmountable barriers but to defeat them we first need to understand them. This is our aim and we hope you will join us in this fight.

Leave a reply to treehill Cancel reply