With March 2024 marking the 40th anniversary of the beginning of the Miners’ Strike, the Class Consciousness Project starts a new series of articles examining the British trade union movement in the 20th and 21st centuries, its inexorable decline in the years since the defeat of the Miners and what as a class we can do to restore trade unions to their former power.

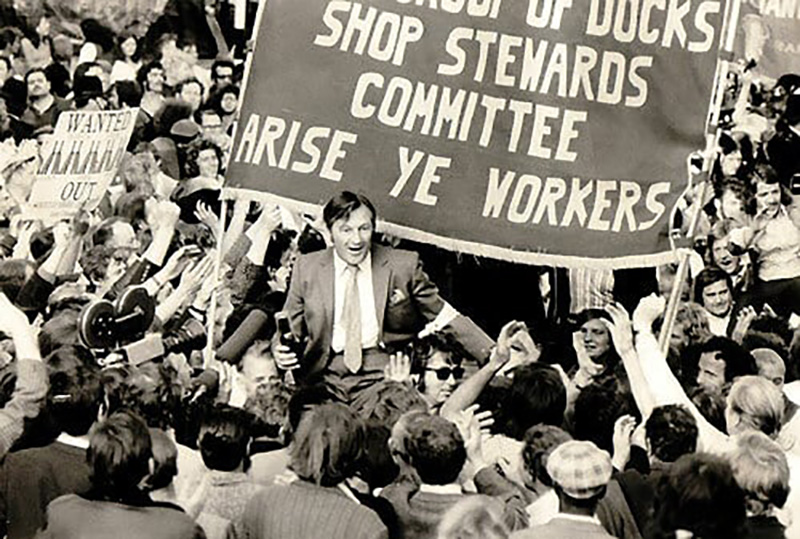

(Picture: John Sturrock/reportdigital.co.uk)

Part 1 – The History: 1964 to 1970

The trade union movement in Britain has been in a steady state of atrophy and decline since the last great working class struggles in this country, that being the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 and, arguably, the News International print dispute in 1986. The defeat of the miners and their union, the National Union of Mineworkers, as well as the printers and their trade unions, the National Graphical Association, SOGAT ’82 and the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers, thanks in large part in both class struggles to the collusion of the thankfully now defunct Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbers’ Union, led by the traitorous Eric Hammond, brought to an end a period of almost twenty years of class struggle in Britain.

Before we formulate a plan to bring the trade union movement anywhere near to its strength of the past, most specifically the 1970s, we need to understand the history of Britain in the period from 1964 to 1986, where trade union strength both reached its peak and inexorable decline.

The fall in the rate of profit to zero in 1965 brought with it an end to the ‘post-war consensus’ period of sustained growth, prosperity and near full employment which began in 1945 and hailed in its stead the dawn of a period of some twenty years of struggle as the ruling class attempted to row back the concessions that they had made to the working class after World War II. In the period from 1945 to 1965, the ruling class were forced to allow the working class to dine on the crumbs from their table and were content for them to do so, as long as they themselves were able to gorge on the huge profits that the working class had created for them in this post-war period. But that generosity soon evaporated once the rate of profit had hit zero, meaning that the working class were to be compelled by their masters to work longer hours for less money and, at least as far as the ruling class were concerned, were to accept this all-out attack on their terms, conditions and standard of living with barely a whimper.

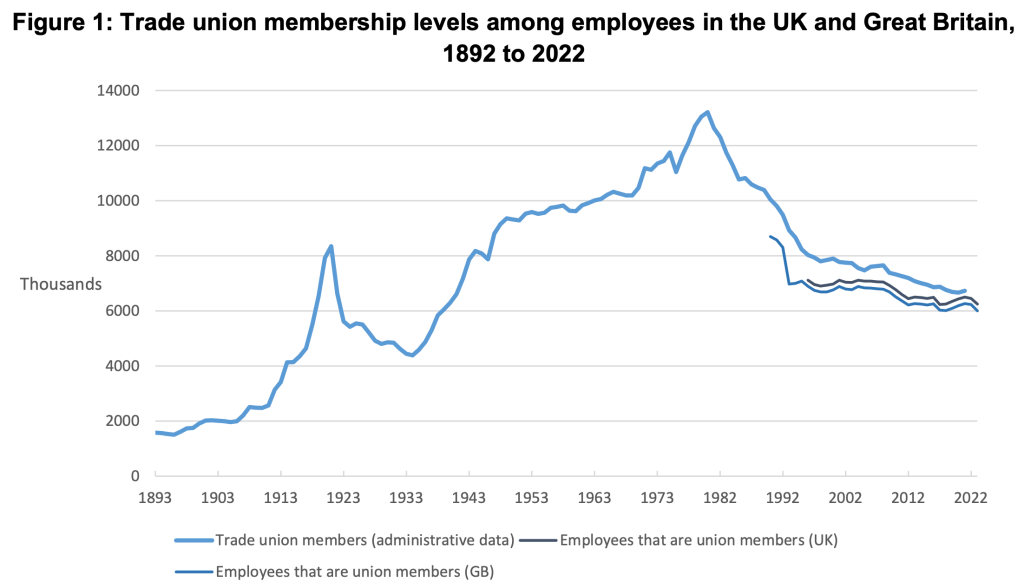

A graph detailing the rise and decline in trade union membership, which hit its peak in 1979

(Source: Administrative data on union membership from Department for Employment (1892-1973); and

the Certification Office (1974-2021). Data on employees that are trade union members in the UK and

Great Britain is based on the Labour Force Survey, Office for National Statistics)

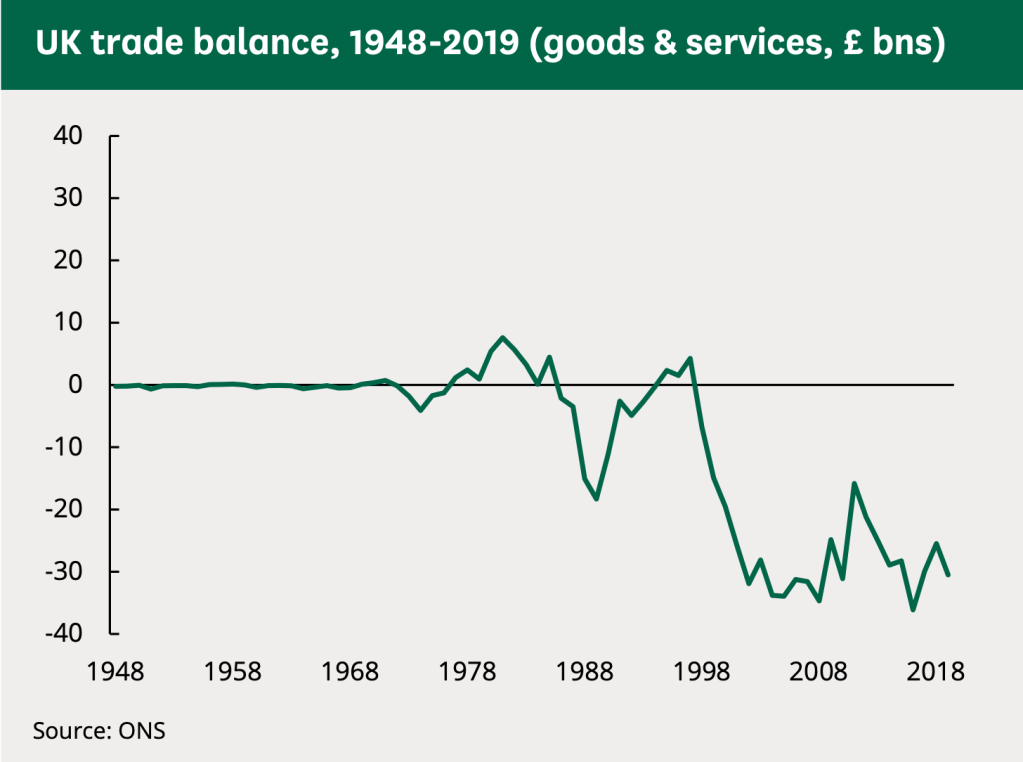

The Wilson Government assumed control in Britain in 1964, shortly before the confirmation of the rate of profit in Britain reaching zero a year or so later, and was faced with a problem. The outgoing Conservative Government had left a balance of payments deficit of £800m (somewhere in the region of £19.4bn in today’s money) and was anxious to restrain wage demands in the working class in order to maintain the credibility of the British Pound on the international money markets.

A Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations was chartered in 1965, to ‘consider relations between managements and employees and the role of trade unions and employers’ associations in promoting the interests of their members and in accelerating the social and economic advance of the nation with particular reference to the Law affecting the activities of these bodies’. Essentially, the Commission would determine if continuing industrial relations needed, from the ruling class’s point of view, management in the form of additional legislation. Conscious of the fact that the Royal Commission could take years to publish its findings (it ended up taking three years), the Wilson Government would immediately seek to restrain wage claims to no more than 3.5% with, as they hoped, co-operation from the Trades Union Congress and their affiliated unions.

Meanwhile, the Conservative Party had been forming the view that trade unions and their members needed to be shackled by legislation since the late 1950s. A key dispute which took place in 1964 between an individual worker and both his employer and trade union crystallised this view. Rookes v Barnard and others was a claim lodged by Douglas Rookes, who was a draughtsman working for the British Overseas Airways Corporation (the predecessor to British Airways) and a former member of the Association of Shipbuilding and Engineering Draughtsman (AESD). Rookes left his union following a dispute, but his workplace was a ‘closed shop’ – BOAC and the AESD had an agreement that BOAC would not employ non-union members, so his fellow workers threatened to go on strike unless Rookes was either sacked or resigned. Having been suspended for months, BOAC dismissed Rookes with one week’s pay in lieu of notice.

Rookes sued the trade union officials, including Mr Barnard, who was the Chair of his former trade union branch and others, claiming that he had been subjected to ‘tortious intimidation’: a civil law term meaning a wrongful act that causes harm. Rookes argued that his contract was terminated despite him not breaching its terms and he would not have been dismissed but for the fact that his colleagues had threatened their employer with strike action. In essence, according to Rookes, it was the ‘closed shop’ agreement which caused his dismissal. Rookes won his case in court, but this was then overturned on appeal. Rookes then took his claim to the House of Lords where, clearly seeing an opportunity to roll back ‘closed shop’ agreements and the workplace dynamic which flowed from them, overturned the decision of the court of appeal.

The Law Lords found that the Trade Disputes Act 1906, which protected trade unions taking industrial action from being sued for damages, did not extend to what they viewed as intimidation on the part of Rookes’ colleagues or his former trade union. The union, which was by this time known as the Draughtsmen’s and Allied Technicians’ Association, had been exposed to considerable legal costs having lost this case and, at the TUC’s congress in Blackpool in 1964, the first Congress since the Law Lords made their decision, delegates warned of the serious threat that the ruling could have on the legal rights of workers to strike.

Class struggle in Britain began to rise in the period from around 1966 onwards. It was in May of this year that the National Union of Seamen (NUS) took part in its first national strike since 1911 as workers demanded a significant increase in pay and a cut in working hours from 56 hours per week to 40. The strike, which was partly organised by former Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott (now Baron Prescott), who was a steward on Cunard Line passenger ships and an activist in the NUS, was very well supported, with ports in London, Liverpool and Southampton most severely affected. It caused real damage to the economy of the country, which still had a serious balance of payments problem and threatened to obliterate the Labour Government’s plan to suppress wage rises to below 3.5%. Prime Minister Harold Wilson was, unsurprisingly, a fierce opponent of the striking sailors, claiming that a Communist insurgence within the NUS had agitated the workers in order to topple his Government, who declared a state of emergency a week after the strike began. The strike ended on 1st July 1966.

In the same year, doctors and dentists received a considerable 30% pay rise from the Government on the recommendation of a pay review body. Whilst there was no overt threat of strike action on the part of either group, they made a more substantial threat – that they would leave the NHS and pursue a living in private practice. The Government’s policy of suppressing wage rises to below 3.5% lay in ruins with the decision, which would have been seen by other workers and would surely have been referenced by trade unionists when making their own play claims.

In 1967, the Wilson Government took the step of devaluing the British Pound exchange rate with the US dollar by 14%, from $2.80 to $2.40. Wilson tried to defend this devaluation, which he said was forced on him because of political instability in the Middle East and the closure of the Suez Canal, as saying that:

“From now on the pound abroad is worth 14% or so less in terms of other currencies. It does not mean, of course, that the pound here in Britain, in your pocket or purse or in your bank, has been devalued.

“What it does mean is that we shall now be able to sell more goods abroad on a competitive basis.”

The devaluing of a sovereign currency is a double-edged sword: On the one hand it makes exports cheaper, but on the other it makes the import of goods and the payment of foreign debt, of which Britain was carrying a considerable amount from the United States, more expensive. Wilson was taking a gamble in devaluing the pound. He was banking on the balance of trade moving into surplus, meaning that the amount of goods and commodities being sold by the country exceeded the amounts being bought in. The Conservatives were quick to criticise Wilson’s Government, with Tory Leader Ted Heath stating that despite over three years of denials by the Government that they would not be devaluing the pound, here they were doing that very thing.

Class struggle continued in the following months and years. In 1968, women workers at the Ford plant in Dagenham in Essex went on strike in a dispute over equal pay with male workers. The women were regraded to a level below that of their male counterparts at a time when women were routinely paid less than men for the same work. The pay differential was approximately 15% less than male workers, which caused the women to walk out on 7th June 1968, with their comrades in Halewood walking out shortly after. As the women were employed as sewing machinists and made car seat covers, the Dagenham plant was eventually brought to a complete halt. Barbara Castle, the then Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, intervened to settle the dispute, which resulted in an 8% pay rise for the women workers, with them all regraded to the grade above the following year. The strike set in train the creation of the Equal Pay Act 1970.

The Labour Government was being driven to the same conclusions as the Conservatives with regard to the management of industrial disputes, which was that only legislation could stymie working class demands for improvements to pay and conditions. Barbara Castle presented the White Paper ‘In Place of Strife’ in 1969 – a far-reaching document which included as part of its recommendations the introduction of workplace ballots prior to strike action. It marked the first clear contestation between the Labour Party and the trade union movement, which began a long-standing and unresolved contradiction between the two which continues to this day.

The White Paper contained three clauses for which legal penalties could be imposed on unions and/or workers which transgressed them: The first was if a trade union refused to hold a ballot in the case of ‘official’ industrial action, the second was if workers went on strike against what was termed an ‘inter-union dispute’, while the third was against workers who refused to return to work in ‘unofficial’ strike action when there was a pause for conciliation with the employer. It created deep divisions within the cabinet, the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and faced fierce opposition from the trade union movement itself – James Callahan, then the Chancellor of the Exchequer, resigned in protest at the proposals and Labour-affiliated trade unions threatened to withdraw support for the Labour Party and the paper was withdrawn after protracted negotiations with the TUC and, crucially, the Wilson Government realising that any bill put before parliament did not have sufficient support from the PLP to get it over the line and into statute.

The Wilson Government lost the 1970 General Election, despite opinion polls indicating a comfortable Labour victory. A late swing to the Tories was found to be the cause of Labour’s defeat, though it would not have been lost on the electorate that the party was deeply split by the ‘In Place of Strife’ debacle and anti-trade union and anti-worker sentiment, reflected in the bourgeois media and its outlets, undoubtedly had an effect on the voting intentions of the professional and managerial cohort of the electorate, a cohort that was gradually turning away from voting Labour.

Leave a comment